15 Nov “Cyber-Banging”: From Richmond’s Streets to the Web

News Report, Lamar Littleton | Nov 15, 2011

Editor’s Note: This report is part of a two-part series produced by The CC Pulse and Richmond Confidential. Read part two here. This report was written under a pseudonym for the author’s protection.

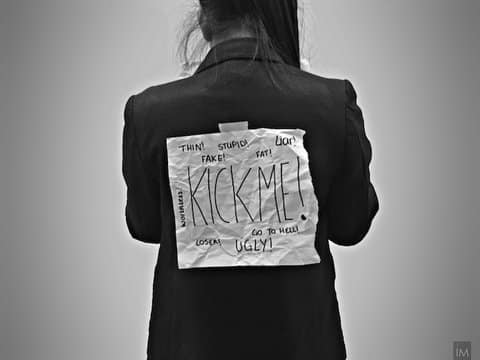

You may have heard of “cyber bullying,” but an even more deadly trend is happening in Richmond and across the country: cyber gang-banging. Young people are using social media as a platform to represent their gang affiliation or their neighborhood. Sometimes the violence spills from the net to the streets and in some cases it has resulted in death. There have been several cases of people who posted comments on Facebook or created YouTube videos that disrespected a rival gang, only to be gunned down in the streets weeks later.

In Richmond, Calif., gangsters, wannabe-gangsters and felons are using social media to incite or glorify violence and to make threats. And even though the drama is happening online, it has very real repercussions.

On Valentine’s Day 2010, Marcel Buggs, 19, entered the New Gethsemane Church of God in Christ with a gun and opened fire on the congregation. His alleged target was a member of a rival street gang in North Richmond. But Buggs accidentally shot the gang member’s two brothers. Neither of the brothers was killed, but the tragedy made national news headlines and alarmed community members.

Months before the shooting, Buggs had posted a YouTube video acknowledging that he was part of a gang and boasting that he would attack his rivals. The video was used as court evidence against Buggs, who was ultimately found guilty of attempted murder.

Another YouTube music video made by the group So Smerkish ENT from North Richmond is called “Wat We Do It 4.” The video contains explicit lyrics, multiple references to gun violence and explicit drug usage. The chorus of the song goes:

Speed what you do it for, I do it for the nickel.

What you bussin’ with, the nickel.

Where you lurkin’, South Central.

All day every day, we rockin’ out a rental.

Bounce out on niggas, we ain’t shooting out no windows.

For those who aren’t familiar with this type of slang, “the nickel” is a 45-caliber handgun, sometimes referred to as a “four nickel,” four short for “40” and nickel slang for “five.” “South Central” means South Central Richmond, which is the neighborhood being targeted. “Rocking out a rental” means rental cars are being used to commit crimes so that the license plate, vehicle number or description can’t be traced.

In the video, a young man is heard saying, ”get whacked like Rickdell, Cool and Rio”— a reference to known rappers from South Central Richmond who were killed.

Another person in the video says, ”Cool was ducking around the car just like a bitch.” The line describes what went on that night in what appears to be a clear admission of involvement in the young man’s murder.

In Richmond and across the country, the music video has evolved beyond a source of entertainment. It’s an admission of guilt — a song that describes what took place during a shootout – and a warning of violence to come.

One of the most popular videos is “South Side Richmond,” by Laz Tha Boy, a tribute to South Richmond, the 35th Street neighborhood and the Pullman Point housing project. It has received more than 200,000 views on YouTube.

The lyrics aren’t as incriminating as in the “What They Do It 4” video, but they are just as violent:

This South Side Richmond, yeah I’m from the 30s,

Hundreds on the K, hand thangs with the 30s.

Heard that nigga speaking on me, if I see him I’ma murk him.

Three round burst leave a nigga face burgundy.

“Hundreds on the K” refers to a 100-round drum clip on an AK 47 assault rifle. “Hand thangs with the 30s” are handguns with 30-round clips. Some people call it a “hand thang” because it’s a slick way refer to a pistol, without the police knowing. ”When I see him I’ma murk him” means that when the rapper sees his rival, he’s going to kill him; and “burgundy” is a reference to blood.

In the song’s second verse, a featured rapper named Tay Way continues the theme of violence:

Me and my niggas out riding.

Niggas dying when we take off.

The message here is clear, and in a city like Richmond, lyrics like these aren’t just music or poking fun. Real people have died.

Gonzalo Rucobo is the co-founder of Bay Area Peacekeepers, a violence prevention program that operates in Richmond and San Pablo. Rucobo, an ex-gang member, is now regarded by many as a hero for his work with youth in the community. When I asked him about cyber-banging, he immediately knew what I was talking about.

“It’s been around for a while now,” Rucobo said. “The big kinda burst of it hittin’ the community was with MySpace. That’s when we began to start noticing that a lot of gang-affiliated [stuff], like a lot of red or blue or neighborhood stuff would be on there.”

Rucobo says that cyber gang-banging serves two purposes: It gives individuals notoriety and it allows for people to communicate with rival gang members in a virtual environment.

“So individuals would let some of their enemies actually log on and accept them as a friend [and] then they would go back and forth,” says Rucobo. ”Not only that, but they’re… going on there and saying, ‘Yeah, we chased you down, that’s why we shot you.’ Or they even go as far as saying, ‘We took out so-and-so.’”

When asked what cyber-banging meant to him, David Serano-Valdivia, 15, a student at Richmond High School said, ”It means you’re down for a certain crew or a certain gang and you post it on the Internet to make it public.”

”There is a lot of cyber-banging in Richmond,” Serano-Valdivia said, in middle school and especially in high school. “It’s weird, because what people won’t do in public, they seem to be able to do easier in the privacy of their own home.

“There’s one guy I’ve seen around, and it’s crazy because he’s the shyest person… but on his Facebook he’s always posting, ‘This gang is better than that gang’ or ‘We’re taking over,’ or this and that. It’s a complete shock because you wouldn’t imagine it from a person like that.”

Rucobo agreed that while there are some “hardcore individuals” posting gang-related content to the web, not everyone cyber-banging is an actual gang member. And in fact, said Rucobo, most seasoned criminals know better than to expose their activities online.

“We began to start seeing the pattern of individuals that really didn’t portray [being a gangster] when they were in school or in the community,” said Rucobo, “but when they got home and behind the screen they were actually able to make it seem like they were this big person, or they were this character…without really knowing the consequences.”

Those consequences, says Rucobo, can mean going to jail or getting real people hurt or killed because of what others post online.

“Today a lot of individuals do it for fame and glory. They think that they’re gonna be on American Gangster. They think that all of a sudden they’re gonna have a documentary on them, or their clique’s gonna come out there on [the TV show] Gangland or somethin’ like that,” he said. “But there are individuals out there that don’t play like that. Once you say somebody’s disrespectful, then they’re looking for you and they’re on the hunt.”

In fact, young people in Richmond have more to worry about than just rival gang members or criminals looking for retribution over something that was said on the Internet.

“A lot of our youth don’t understand that they could be incriminated [legally] by the things that they’re putting out there,” Rucobo said.

A law enforcement officer who spoke to The CC Pulse under the condition of anonymity said the police follow cyber-banging and other online communication.

“Social media has evolved as the primary way of communicating in our culture,” he said. “We know that a good way to get intelligence about people, like what’s [happening] on the street, is to follow social media websites.

The cops, said the investigator, have a right to identify or take action against individuals based on what they put out over the Internet, despite the fact that some seem to think that on the web, anything goes.

“Freedom of speech is very important and it has to be protected,” said the officer. “[But] there are also laws that make it illegal to threaten the safety of somebody, and that’s really where you cross the line… It becomes a violation of the penal code.”

“YouTube videos and Facebook videos that are public often show very recognizable people making threats, talking about things that just happened or things that are going to happen in the future,” he explained, “and these are very important ways to engage or to stop violence from happening.”

Read part two in the series, The “Prince” of North Richmond’s Projects.

No Comments