16 Jul Q&A: Where Did Prosecution Go Wrong in Zimmerman Trial?

Interview, Dr. Joseph Marshall / Street Soldiers Radio Posted: Jul 16, 2013

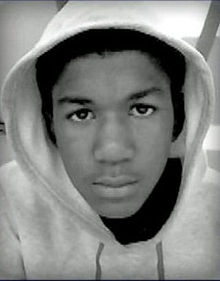

Editor’s Note: In an excerpt from an interview with Street Soldiers radio host Dr. Joseph Marshall, Oakland-based civil rights attorney John Burris discusses the recent not-guilty verdict for George Zimmerman in the Trayvon Martin murder case. Burris is the attorney who represented the family of Oscar Grant, a young African-American man who was killed by a Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) officer early on New Year’s Day, 2009. In that case, the shooter was found guilty of involuntary manslaughter.

I guess the first question on everybody’s mind is: How does a jury come up with this ruling?

I know it was a surprise to many within the African-American community but it really should not be, given the way the evidence… was not presented in a way that you could prove second-degree murder. At best, you could prove involuntary manslaughter. And I say all that because the prosecution, which had the burden of proof, never put forth a theory of how this happened. The jury was really only left with the defense’s version — and the defense’s version was that it was a self-defense case. And there is evidence, obviously, to support that. I mean, all you have to do is know that George Zimmerman had a laceration on the back of his head, he had a bloody nose, and there was another independent person who said… they [Zimmerman and Martin] were involved in a fight. And so, when you’re involved in a fight — putting aside who started it, because they couldn’t prove who started it — if one person is getting beat up really bad, then they have a right to defend themselves. And [then] the question is, should it have been deadly force or not?

My argument was, and is, that it should not have been deadly force, because Zimmerman was not beaten in such a way that a reasonable person would have thought their life was in danger. On the other hand, the prosecution never put forth an argument to show that it was not reasonable for him to believe his life was in danger. What really happened is, the defendants put on [the stand] an expert who basically said that the injuries he did receive are the kind of injuries that can be serious, and that a person receiving those injuries may think their life is in danger. The prosecution never countered that particular evidence… And so, it was very hurtful to see this unfold.

Now, did I think the prosecution did a good job? No I do not. I think they did… a terrible job. I don’t know all the evidence that they had, but I do know that the evidence they did present. They did not present it well. They did not screen their witnesses; they did not protect their witnesses. They let this young lady, Rachel Jeantel, testify, and they never prepared her so that she would know how challenging the cross examination was going to be.

You’re telling me that the case was not charged properly?

It was not charged properly. It never should have been charged as a second-degree murder case. Now, I understand why they did — there was a lot of publicity, a lot of public pressure. But in terms of a professional judgment, they made a decision based on the fact that George Zimmerman had made some improper statements. He used profanity [during his encounter with Martin] and he basically profiled Trayvon Martin — I think that that’s a given, that he was profiled. The judge would say you couldn’t use race [as a trial argument], but he was profiled. So, that gets you into the game. But ultimately, you can stop someone; you can follow someone — that doesn’t automatically make an illegal act. You can do that. It’s only when you become aggressive and you physically touch them. But beyond that, you can follow them. You can say that this person looks like he’s committing a crime or something, and you should call the police. And he [Zimmerman] did call the police, but he should have stopped right there. What everyone was upset about, and rightfully so, is that he was told [by the police dispatcher] that he didn’t need to follow [Martin], but he continued to follow. And by doing that, he created this confrontation.

The problem with the case was, you don’t know what happened once the confrontation took place. We do know this: that there is another witness that says that George Zimmerman was on the bottom, and Trayvon Martin was on top. And Trayvon Martin was beating this guy up, and then a few seconds later you hear this shot, and then you see Trayvon Martin lying off to the side. And so it looked like Trayvon Martin was on top of this guy, getting the best of him, because this guy has a bloody nose and he has lacerations on the back of his head, so George Zimmerman thought his life was in danger and so he shot him. The point is, did he really have to do that or was that excessive? And that’s where the manslaughter case comes in — it never was a second [degree murder]. And so the prosecution overcharged the case and couldn’t prove it. And then they didn’t even argue very well about the manslaughter.

They let a jury get selected with all women, five white, one maybe Hispanic, and no blacks — the blacks got kicked off the jury. There was no one to explain to the other members of the jury that this was racial profiling and this is how it happened, and this is what it means. And so as a consequence of that, the jurors really weren’t placed in a position where they could make an intelligent decision on facts that would have been helpful for the prosecution of the case.

As a lawyer, you must have been sitting there saying, ‘What are these guys doing?’

First off, the opening statement [by the prosecutor] that everyone thought was terrific — it wasn’t terrific. It was very emotional. There were no facts in it… Well, the truth of the matter is, cases are not about heart; they’re about evidence, and rules of evidence.

What we were upset about was that a young boy goes to the store, buys whatever he’s buying, he’s walking back, he’s talking on the phone to a girl, and someone says he looks suspicious. And they follow him. And within minutes, the kid is dead. Well, there’s something fundamentally wrong with that. Except that the lawsuit wasn’t the place for that [racial profiling argument] to occur.

What can be done now? I know there’s talk of a civil suit.

There are a lot of discussions going on. First off, they want to see if the Justice Department in Washington, D.C., will file criminal civil rights violations based on this being a hate crime. I can tell you, I’ve sent maybe 10 to 15 cases to the Department of Justice for prosecution. In many of them, people have been shot any number of times. The Oscar Grant case, I sent there. And I got a case out of Manteca I’m working on now — a kid was shot 20 times. And the Justice Department has not prosecuted any of those cases. And the reason being is that unless they have clear, bona fide evidence, like a Rodney King, [a case] which I did many years ago, with video tape, it’s pretty clear that they’re not going to take action on a case like this. What they’re looking for is impact cases — the city of New Orleans, when they had all those problems; the city of LA; they would have done Oakland [for the Oscar Grant case] but for the fact we did Oakland. So they’re looking for impact cases that are going to impact discrimination… Now, when Al Sharpton and the NAACP get involved, it may be that the Justice Department will be more responsive….

The other thing is, they can sue Mr. Zimmerman in a civil case. Now, that’s easy to do — you can sue him, and then he’d be required to testify and you may get a judgment in your favor. But if it [the civil trial] is in Seminole County… you may not. The difference is this: the Martin family, or the mother, does not live in that county. And Trayvon didn’t live in the county. The lawyer doesn’t live in the county. So in a way, it was outsiders coming into the county, and George Zimmerman was one of them [a local]. That’s an undercurrent of a political thing that a jury is not to consider, but this is an all white jury from Seminole County who, you know, basically didn’t have the same value system as you and I may have… You or I might say, ‘Why would you say he’s suspicious?’ Walking in the rain, on the phone, trying to get back to his house. [Zimmerman] could have easily said, ‘What are you doing? I’m the neighborhood watch commander,’ and say that in a polite way. [Martin] could have responded, ‘I’m here with my mom, my dad is here, and I live over here….’ That was a confrontation that did not have to happen.

I would say to all young people — you have to look at how to de-escalate a situation, particularly when you know you can be viewed suspiciously, even when you’re not doing anything wrong. You’ve got to have a way to handle that, just in case. And that is, you talk to the person to find out what the problem is, if you can, in a polite way, and tell them who you are and what you’re trying to do, which maybe will prevent the problem from escalating — because in certain states, people carry guns. And the other thing you should keep in mind: there are going to be a lot more neighborhood patrol groups. I know in the city of Oakland we have them, and these people have guns. So if you walk into my neighborhood or a neighborhood like mine, and they don’t know you, you may get accosted. So, young people have to be very mindful of that….

1 Comment