17 Jun Remembering Kevin Weston: Super Communicator and New Media Pioneer

By Russell Morse

Kevin Weston, accomplished journalist and long time New America Media family member, died Monday at his home in Oakland after a nearly 2 year fight with leukemia. From 1999 to 2010, Kevin worked as the organization’s Youth Communications director, but his legacy reaches far beyond that title. Kevin was a teacher, an activist and multimedia visionary. He was a mentor to hundreds of young writers, filmmakers, artists and photographers finding their way, many of whom have gone on to great success.

I was one of the young people Kevin guided and encouraged as editor of Youth Outlook. My story is a familiar one among the veterans of YO: I spent my teenage years in juvenile hall and came to New America Media through YO’s sister program, The Beat Within. I started writing for Youth Outlook and early in my time there, Kevin came in as the head of the magazine. He trusted our impulses and gave us the tools and encouragement to tell the stories we deemed most pressing.

Mizgon Zahir, a former colleague of mine, came to our offices at Kevin’s insistence after a chance meeting in 2001. Reflecting on his influence in her life, Mizgon said, “As a young writer, I was afraid to talk about taboo topics related to the Afghan community, but Kevin taught me how to find my voice. He taught me about courage. He showed me how to take risks to help others and advance myself.” Mizgon’s story, the first she’d ever written, ran on our cover. That was a month before 9-11 and long before the government’s invocation of the oppression of Afghan women as a justification for war. Beyond foresight, it was downright clairvoyant. But we came to expect that from Kevin. He was dialed into the world in a way that seemed almost extra sensory.

His legacy is solidified as a media pioneer in what’s now referred to as The Bay Area Style of Journalism, an early ancestor of citizen journalism that combined multimedia storytelling and activism with the emerging technological tools of the 21st century. The Pacific News Service model of journalism encouraged community members, mostly media outsiders, to tell their own stories relating to themes ignored or fumbled by mainstream media, like incarceration, environmental justice, violence and immigration.

Kevin’s contribution to this model was that he was among the first to encourage the use of internet-based media platforms to bypass traditional news outlets. It is called The Bay Area Style because it was informed by the proximity to Silicon Valley during the communication revolution, a tradition of progressive politics in the region and the Bay Area’s place in history as the home of the free speech movement and the Black Panther Party. Kevin combined these sensibilities into a vision for a future we now take for granted, but was bizarre and beguiling in 2000 when he first encouraged us to approach media and activism in this way. He often said that “protests are corny,” and that the future of activism and organizing was a convergence of media, networking, technology and communications. The role that twitter played in the Arab Spring is one example of this vision come to fruition, ten years later.

Kevin was also an insistent outsider, suspicious of formal institutions, including traditional media organizations and universities, for their corruptibility and traditional, stubborn modes of thought. When I was considering majoring in journalism at San Francisco State University, he told me “I’ve seen a lot of good writers ruined by J-School.”

Kevin’s work at New America Media was reflective of the times we were living and working in. The first decade of the 21st century was an incredibly violent, tumultuous time and Kevin saw and professed a connection between violence in poor communities and the ongoing wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. He encouraged us, as reporters, to find global connections to the local stories we pursued.

Even Kevin’s style of dress was reflective of his dynamic and unique perspective on the world. In the years that we worked together, his typical work outfit consisted of a dashiki, worn under a tuxedo jacket with camouflage cargo pants, Adidas shell toe sneakers and an Oakland A’s baseball cap with his bushy afro pushing out of the sides. Many of the aspects of Kevin’s identity were present in this outfit: he was a Black man, a playboy, a soldier, a hip-hop head, a sports fan and a proud Oakland native.

Even Kevin’s style of dress was reflective of his dynamic and unique perspective on the world. In the years that we worked together, his typical work outfit consisted of a dashiki, worn under a tuxedo jacket with camouflage cargo pants, Adidas shell toe sneakers and an Oakland A’s baseball cap with his bushy afro pushing out of the sides. Many of the aspects of Kevin’s identity were present in this outfit: he was a Black man, a playboy, a soldier, a hip-hop head, a sports fan and a proud Oakland native.

Kevin’s editorial style was famously minimalist. He offered selective guidance but readily hounded writers on deadline in the gruff style of Perry White, Clark Kent’s editor at the Daily Planet. An often-recounted story involves Kevin trying to encourage a young woman who was well past deadline to get her story finished. After several patient minutes on the phone, Kevin stood up, held the receiver a foot from his face and said, very slowly and quite loudly: “It’s. Not. That. Hard! Just write what happened!” It’s a funny story, but it’s also an implementation of his journalistic philosophy. His job as he saw it was not to tell us what the story was or tinker with our copy. He trusted us to gather the facts, to “write what happened” and put our version of it out to the world. In my case, he called me when I was past deadline and simply asked “Do you still write?”, adding an affectionate expletive in the place of my name.

At the front end of the editorial process, though, Kevin was incredibly engaged, gentle and encouraging. We often had contributors who had never written anything in their lives and thought they didn’t have a story to tell, but Kevin brought it out of them. Malcolm Marshall, a long time friend and collaborator of Kevin’s compared it to a magic trick. “Kev could pull something out of a kid who didn’t even know they had it in them. He could pull a rabbit out of a hat.”

Kevin’s neatest trick, though, might have been his ability to tame and balance the different projects of New America Media itself, an outrageously diverse, often chaotic newsroom. In the early 2000s, we had scholars, young people fresh from juvenile hall, activists, members of the ethnic press, homeless youth living off the grid and recent college graduates, all sharing the same space. We were all in the service of a common goal, but balancing those energies took an incredible amount of finesse and it often fell to Kevin to maintain the peace. Or to disrupt it, depending on what he saw fit.

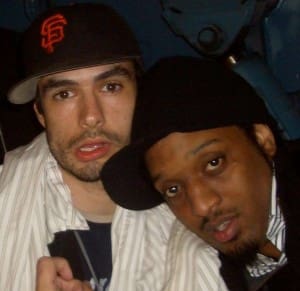

The Youth Communications projects of NAM came about in the early 1990s, when America’s young Black men were sensationally and shamefully characterized in the mainstream media as “Super Predators”. Sandy Close’s counter was that this generation of young people was not super-predatorial, they were super-communicative. Kevin was a supercommunicator: a journalist, a rapper, an editor, a DJ, a public speaker and a conversationalist who lived to engage the world, challenging hypocrisy and abuses of power right up to his final days.

In 2005, NAM hosted an Ethnic Media Expo at Columbia University in New York City. One late night, after celebrating the success of the event, I found myself in a rap cypher with Kevin and several New York City rappers on a street corner in the Lower East Side. It quickly became a battle between us and the New York guys, one of whom rapped that he’d finish us “like the Son of Sam”. Kevin was next and he rapped “serial killers? yeah, we can talk about that/I’m from the bay, the home of the Zodiac/but Einstein Berkowitz is up under the jail/while the Zodiac’s still out there and YOU’VE GOT MAIL!” Everybody cheered. That line ended the battle and the guys all slapped our hands before we walked on. Earlier that day, I was with him at a reception in The New York Times offices, where I watched Kevin, while eating shrimp and drinking a Heineken, tell one of their higher-ups, “Print is dead.”

In 2005, NAM hosted an Ethnic Media Expo at Columbia University in New York City. One late night, after celebrating the success of the event, I found myself in a rap cypher with Kevin and several New York City rappers on a street corner in the Lower East Side. It quickly became a battle between us and the New York guys, one of whom rapped that he’d finish us “like the Son of Sam”. Kevin was next and he rapped “serial killers? yeah, we can talk about that/I’m from the bay, the home of the Zodiac/but Einstein Berkowitz is up under the jail/while the Zodiac’s still out there and YOU’VE GOT MAIL!” Everybody cheered. That line ended the battle and the guys all slapped our hands before we walked on. Earlier that day, I was with him at a reception in The New York Times offices, where I watched Kevin, while eating shrimp and drinking a Heineken, tell one of their higher-ups, “Print is dead.”

No Comments