18 Feb Historic Ties: As Chicago’s Pullman Neighborhood Seeks National Park Status, Richmond’s Own Pullman Story Remains Unpreserved

By April Suwalsky

For over a century following the Civil War, African American men employed as “Pullman Porters” — railway employees who assisted passengers on Pullman company trains — were the eyes and ears of the nation.

The porters founded the first black labor union and distributed black newspapers, reaching rural communities and igniting social change. They led national movements that gave rise to improved conditions for the working class, civil rights and formal recognitions such as the creation of the Labor Day holiday.

The porters’ stories and legacies are preserved most notably in the historic Pullman neighborhood built in the 1880s in Southside Chicago. The neighborhood, which was already a city landmark, National Trust for Historic Preservation “National Treasure” and listed on the National Register of Historic Places, became the country’s newest national park when President Barack Obama officially declared Chicago’s Pullman Historic District a national monument on February 19.

While Chicago’s neighborhood gains recognition, Richmond’s rich Pullman story remains less known and in danger of crumbling away.

Beginning in 1867, industrialist and Pullman Palace Car Company founder George Pullman began hiring African Americans – many who were former slaves – as porters and train personnel in Chicago. Despite low wages, the porters delivered impeccable service, and were the primary reason long-distance rail travel was considered luxurious.

By the 1920s, more than 20,000 African Americans were employed across the country as Pullman Porters, the largest category of black labor in the U.S. and Canada at the time. Passengers called the men “George” after George Pullman — regardless of the porters’ own names — a practice that harkened back to slavery.

In 1926, Pullman company leadership was persuaded — primarily by white men named George who did not want to be associated with the porters — to display the porters’ given names on placards in the train cars. (Of 12,000 employees surveyed, only 362 were actually named George.)

In Richmond, as in the rest of the country, railroads shaped how the city was divided, socially as well as physically. Part of this division is still felt in neighborhoods like the Iron Triangle, which is defined by the Union Pacific and Burlington Northern Santa Fe tracks to the east and west and by the Richmond Greenway to the south, which grows along abandoned Santa Fe tracks.

Passenger rail cars were serviced at the Richmond Pullman Shops, a large plant at Carlson Boulevard and South Street that was the line’s western end.

Black porters and workers were not allowed to stay at the “layover” Pullman Hotel nearby, on the corner of Carlson — that was intended for white-only workers. Instead they stayed at the small 20-room International Hotel at 396 South Street, built circa 1900 and located about a block away from the Pullman Hotel.

In addition to being a respite for the Pullman porters, offering live music and warm, affordable meals, the hotel was a place of social mobilization and empowerment.

The Pullman Shops in Richmond closed in 1959, and subsequently the Pullman Hotel and several other on-site buildings were demolished. However, two main buildings and the International Hotel remain.

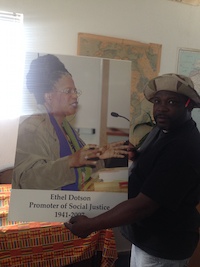

The late environmentalist and preservationist Ethel Dotson purchased the hotel with hopes of restoring it. Dotson, a tenacious community advocate, succeeded in a collaborative effort to have the Pullman Historic District and the hotel named as city historical landmarks, but restoration efforts stalled due to lack of funding.

The late environmentalist and preservationist Ethel Dotson purchased the hotel with hopes of restoring it. Dotson, a tenacious community advocate, succeeded in a collaborative effort to have the Pullman Historic District and the hotel named as city historical landmarks, but restoration efforts stalled due to lack of funding.

Since Dotson’s death in 2007, residents and stakeholders have endeavored to honor her wishes to restore the hotel, and raise awareness about its importance to Richmond and U.S. history. However, there is disagreement about the best path forward, and the needs of funding and public partnerships have proved sticking points.

“There must be some way to establish the historic value of Ethel’s building so that its worth to black history will bring the help we’ll need to get it purchased toward the goal of restoration,” wrote Richmond’s well-known historian, and national park ranger, Betty Soskin in 2007. “The Pullman Company figured powerfully in that era and (surely) in the life of the International Hotel. That history will be important now to the justification for national landmarking and eventual restoration. The International Hotel must first be saved.”

Mayor Tom Butt, a community champion and advocate for historic preservation projects for many years, said that to make the restoration a reality would require up to a million dollars, and cooperation from the Dotsons to convey it to a non-profit organization.

“This is a very important part of Richmond history, and I would like to see the building saved and made accessible to the public,” he said.

Dotson’s son, Karithi Hartman, inherited the hotel after her death and says he is not interested in giving up ownership of the property. He does, however, agree that it’s important to preserve the Pullman porter legacy in Richmond.

“It will definitely be a part up in there that will be dedicated to the Pullmans,” said Hartman. “But selling, that’s not going to happen.”

1 Comment