15 Nov Leadership Skills are Honed Through Everyday Arguments

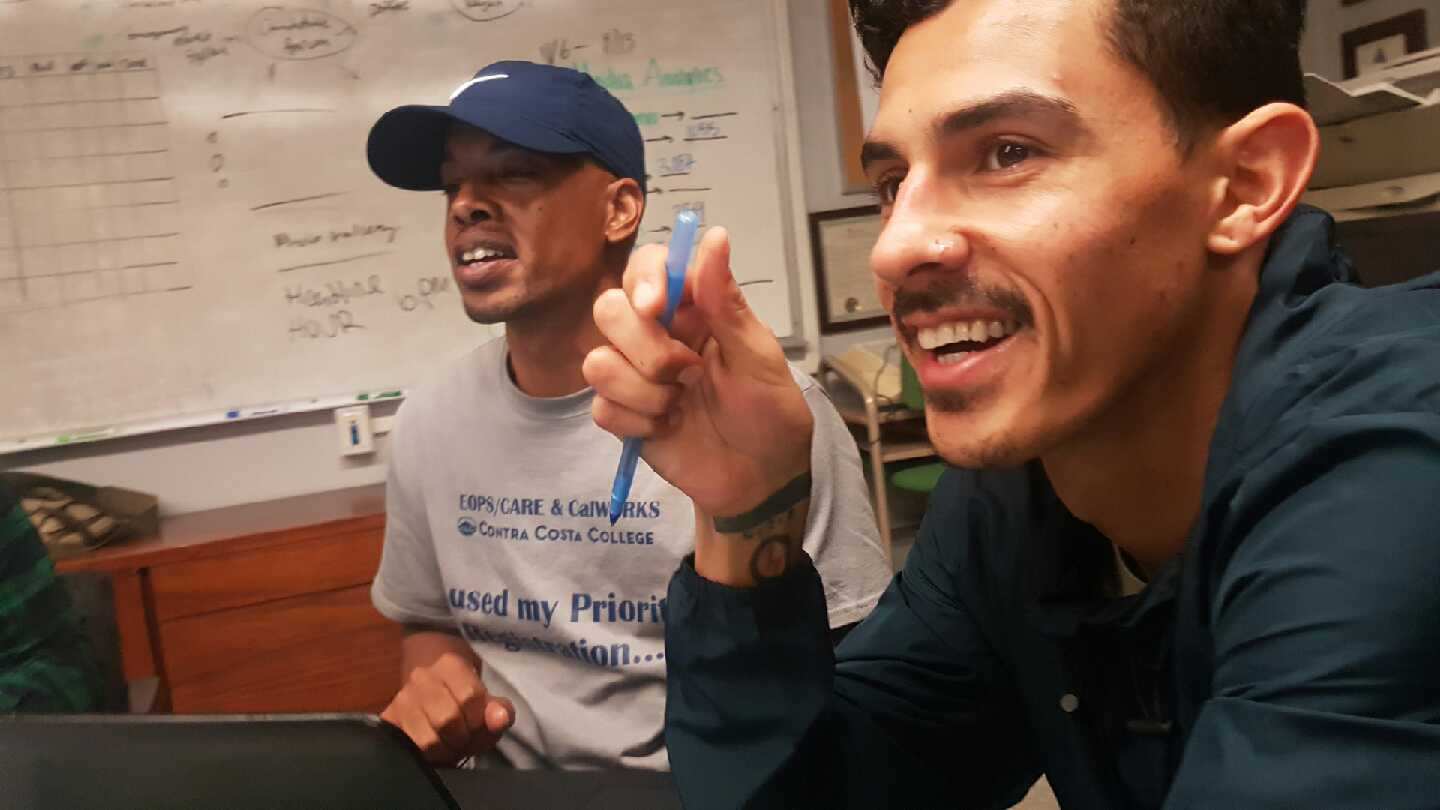

Above: Advocate editors Rob Clinton (left) and Michael Santone (right) listen to another editor during The Advocate’s editorial board meeting at Contra Costa College.

Commentary, Denis Perez-Bravo

Every Monday and Wednesday, I stand in front of the staff at Contra Costa College’s newspaper, The Advocate. Reporters, photographers, designers and illustrators all await their assignments. One of them, a reporter and one of the best writers, is Rob Clinton.

As I give him the assignment that I want him to work on, he will ask me: “What are the readers supposed to get out of this story?”

I can be prepared for this question, but it always makes me pause, think and respond as clearly as I can.

For the majority of my life, I stayed quiet and listened to others’ opinions, which is still my greatest strength as a communicator. Now, as a leader — editor-in-chief of the Advocate — I’m directly in charge of a student’s growth, so I must embrace both sides of the exchange.

It’s important that I, as a leader, am concise with my words and intentions.

After years of working with Rob, these kinds of questions have improved my speaking skills. I am realizing more and more every day that effective communication is key to leadership.

And I have Rob’s time and patience to thank for realizing it.

Rob is a very opinionated and smart person. I work with him regularly in the Advocate newsroom. He is part of the editorial board and I lead as editor-in-chief. Because of that, we’ve had many energetic debates that have incited me to speak more precisely so I’m not misunderstood.

Since I first came to the Advocate in the fall 2015 as a staff photographer, Rob would grill me about how I argued or described something.

For example, I would try to explain a movie I saw when I was younger but had forgotten the name of it. I would use generic terms for specific characters in the movie, like “big man,” “black hair,” “white woman with a purse.” Not particularly descriptive or helpful.

I used a similar method of specificity when trying to argue a point.

In our editorial board meetings, I was not initially in a position of leadership, but I thought my ideas were as good as any others. When I had the courage to speak up, I would become flustered, tied up in words, and stumble over my nervousness. Looking back, I realize I was expecting Rob and the rest of the editorial board to know what I was talking about without really explaining it well. That’s a lot to ask of anyone.

When I first became editor-in-chief, answering Rob’s question — “What are the readers getting out of this?” — wasn’t one of my particular strengths. I had first-year students running amok, attempting to learn the basics of journalism while their editor was a bad communicator. This was not the model the Advocate held itself up to be, but it is where I started. I know I can only get better and it would start with Rob’s simple question.

Since then, every time I talk to Rob, I pause and think about how to word a sentence in the most logical way possible.

In the Advocate newsroom — just like any newsroom — we have many disagreements about how to do things: from the final layout of the print publication to the music choice in an online video. Now that I am Editor-In-Chief, I have to make every decision or delegate them to qualified staff. The same goes for story assignments.

Sometimes the story I thought I had asked for doesn’t come back right. Unfortunately, and too often, the confusion would start at the beginning of the process — when I explained what I needed the reporter or photographer to do.

I remember a specific incident where I sent a first-semester Advocate reporter to cover an event on campus. The event — “Financial Day Awareness” — seemed pretty straightforward to me because I have attended the event many times. But I failed to tell the student that the specific goal of the story was to talk about the programs on campus. My reporter turned in summaries of all the booths at the event and even what seemed to be ad copy for a commercial for Wells Fargo.

Rob saw these things happening and called me out on it because I had given him similarly vague instructions. Of course, because he is a more seasoned journalist, he did not need my direct guidance to write a good article.

It wasn’t long before Rob would confront me. He wanted to talk about my conversations with the staff during editorial board meeting or other aspects of assigning stories. Rob saw that I wasn’t speaking clearly, so he began pushing me to say what I mean. I took his remarks to heart. I can’t say my use of language improved instantly, but I see improvements every day.

Thanks to people like Rob, I am much more careful about speaking clearly, being direct with instruction, and other crucial parts of being a leader.

Thanks, Rob.

No Comments