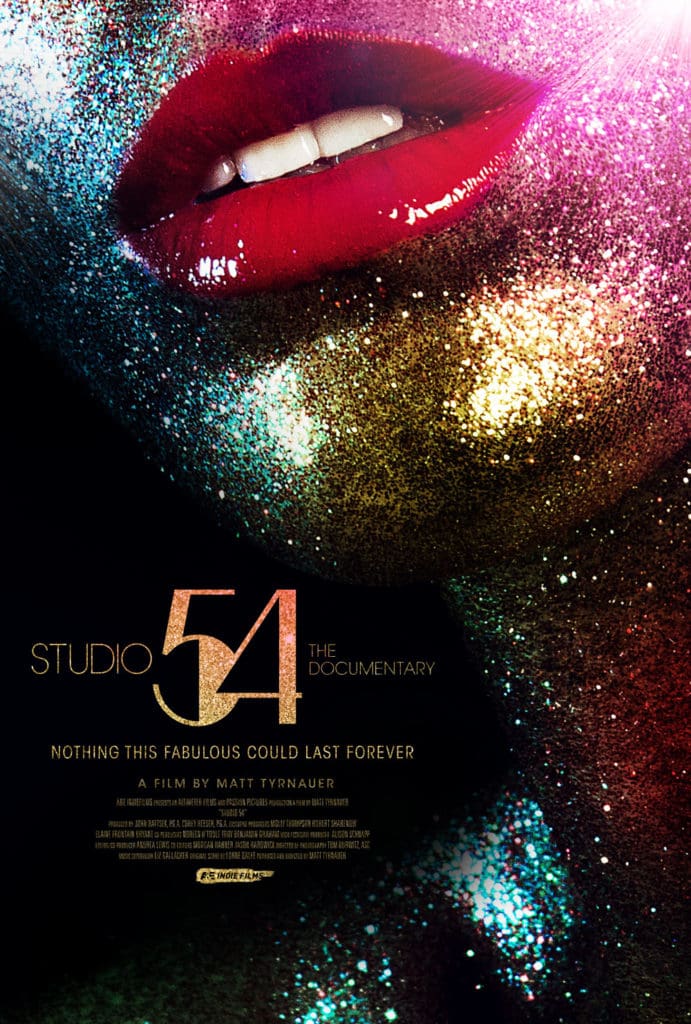

12 Oct Freedom on the Dancefloor: A Review of Studio 54

By Keisa Reynolds

It’s 1977. You’re dressed in your most fabulous outfit for a night out in New York City. There is no reason for you to not attract attention. You hop in a cab to the function with your friends. You walk up to a large crowd of people with the same mission: join the party at Studio 54, the place to be.

Studio 54, the legendary nightclub started by Steve Rubell and Ian Schrager, was in a league of its own since its opening. The documentary film Studio 54 follows the creation of a cultural establishment and the masterminds behind the scenes. Rubell and Schrager were born and raised in Brooklyn, and later met through their fraternity at Syracuse University. After opening a successful disco, the best friends decided to open the ultimate nightclub in an old opera theater on Manhattan’s west side.

There was already overwhelming press coverage prior to the opening of Studio 54. It was practically an overnight success that no one could have predicted. It became a haven for its attendees. It was where they were able to take refuge from the struggles of the world, including the violence and poverty that took place outside.

You had to be somebody to get inside of Studio 54. You did not necessarily need to be a superstar like Diana Ross or Liza Minnelli — who were beloved regulars — but you needed to look good. Aesthetics were everything, so many hopeful attendees dressed in their most lavish garb. That, alongside the actual performances occurring inside, were part of the nightly show — and despite its popularity, not everyone liked that about the nightclub. There were critics who thought the owners and staff were arrogant and “playing god” with their cherry-picking as they selected from hundreds of people crowding the club’s front door.

The film’s release arrives a year past the 40th anniversary of Studio 54. The documentary helps situate the club’s significance within the socio-political landscape of the United States at the time. Studio 54 symbolized a time where desire and expression pervaded the country. People, according to interviewees in the film, wanted a place to let loose and feel nothing but the music. They received freedom, despite its impermanence, in the form of partying. The owners gave them a gift.

Rubell and Schrager, however, epitomize white privilege. There is no denying they worked hard to maintain such an environment, but they also took advantage of the success they quickly gained. They caught the attention of the IRS and in 1979, Rubell and Schrager were arrested for tax evasion and skimming $2.5 million of the club’s profits. They were convicted and sentenced to three years in prison, of which they served shortly over a year. Their version of Studio 54 closed in 1980 but soon opened under new owners.

Out of prison as former owners of Studio 54, they had to work their way back into the spotlight. It took years, but it was not a complete surprise they were able given second chances that allowed them to open a new nightclub, the Palladium, in 1985. But the legacy of Studio 54 had started to dwindle as disco become increasingly unpopular.

Studio 54, as regulars knew it, was long over and so was the neighborhood. A sign of the start of the Reagan era, Manhattan underwent gentrification. According to people of that time, Manhattanites were concerned with money and status over self-expression and community. If anything, conformist ideals were making their way through the borough as with the rest of the country. During this time, the LGBTQ community was facing devastating losses as their loved ones — primarily gay men, many of whom attended or worked at Studio 54 — were dying from complications of HIV/AIDS. Co-owner Rubell was one of the people whose lives it claimed.

The downfall of Studio 54, outside of the criminal activity, has to do more with the way outsiders viewed the culture surrounding the club. They wanted nothing to do with immoral actions, certainly not public nudity and sex. Recreational drug use was way out of the question. Don’t forget the brown and Black people, gay people, trans people. Those on the margins of society found a home less-liberal people didn’t think they deserved. Many of the conservative critics were probably uncertain about liberation. What did liberation entail and from what did they need liberation?

However fans want to portray it, the nightclub was a playground for unabashed debauchery. It is debatable whether or not it was a terrible thing.

This film is worth watching, though I do have one complaint: if Studio 54’s legacy is that it was a safe space for marginalized people, there should have been more representation among the interviewees. The film properly attributes disco to Black people. but we did not get to see many recalling their time at the nightclub.

What almost makes up for it is rare footage of a young Michael Jackson, a frequent visitor. I am sure we miss an opportunity to hear how far Studio 54’s impact went. That complaint aside, I learned a new piece of history and I loved seeing the footage of people dancing their hearts out. To them, the awfulness of the world did not matter — fun did. Their joy was infectious.

Soon after watching, I put on the Donna Summer Radio on Spotify, and got dressed for a night out. It was my turn to dance.

Studio 54 The Documentary opens on Oct. 12. You can catch a showing at Landmark Shattuck in Berkeley and Landmark Embarcadero in San Francisco

No Comments