14 Mar As Funding for School Resource Officers Comes Up For Debate, So Too Does Their Impact

By Abené Clayton and Malcolm Marshall | Photo by Sukey Lewis

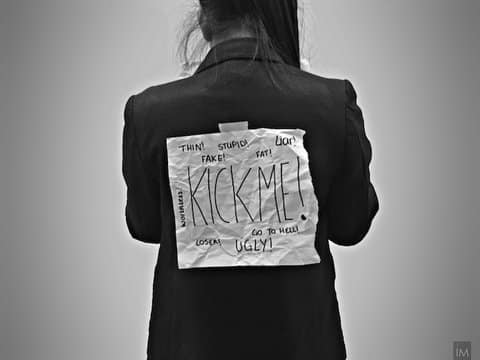

Discussions around school safety include everything from school shootings and bullying to counselors and restorative justice practices.

As these conversations expand, the presence of school resource officers, or police officers stationed on K-12 campuses, remains a central issue.

In Richmond and other West Contra Costa County schools, there’s debate over whether their presence contributes to “the school-to-prison pipeline,” which the American Civil Liberties Union describes as “a disturbing national trend wherein children are funneled out of public schools and into the juvenile and criminal justice systems.”

In West Contra Costa County, police departments dedicate 13 officers to 12 middle and high schools, six of which are in Richmond.

During its Jan. 29 meeting, the Richmond city council broke down the finances and responsibilities that come with the SRO unit. With the contract still in negotiations, the city, school district and police department have shared up to $2.3 million for SROs annually for the last five years.

The school district recommends a $150,000 cap on each officer.

That would require the city to pay upwards of $1 million to cover the rest of the officers. Councilmember Jael Myrick said the money would likely come out of Richmond’s general fund. He said it would be worth it if it keeps schools safe.

“If it’s the right thing to do, we need to figure out how to fund it,” Myrick said.

Money is just one consideration, though. Another is the impact on the Positive School Climate Policy, created in 2016 to address disparities in suspensions and academic achievement among underserved groups, including English-learning, black and low-income students. The policy calls for SROs to use “pre-arrest diversion” techniques and to stay out of classroom disciplinary issues.

Le’Damien Flowers, 28, is a native of North Richmond who works with the Safe Return Project, which works with and advocates for the needs of the formerly incarcerated.

Flowers said his time at Richmond High School was cut short, partly because of run-ins with the SRO.

“It definitely played a huge factor in to me being pushed out of high school,” Flowers said. “He used to mess with me every day. He pushed me out of high school and into juvenile hall and to the streets.”

At the time, Flowers says he was dealing with depression and anxiety — like many young people who grow up in low income communities — not to mention turf wars in the city, all at a young age. Flowers started self-medicating.

“I smoked marijuana to deal with my issues and that was the main reason he policed me,” he said. “[The SRO] didn’t do it physically, but he tried to use his presence over me. It just felt like he just made my situation worse.”

According to a new report from the ACLU, up to 10 million students are in schools with police but no social workers and “no data indicates that police in schools improve student safety, student educational outcomes, or student mental health.”

Flowers said he was on his way to being another victim of the school-to-prison pipeline until he was diverted to the Safe Return Project. At age 24, he got his first mentor, someone Flowers says could have helped him in high school.

“I wasn’t a bad kid; I just needed support,” he said.

Now, he’s conducting focus groups with high school-age students in Richmond. One of the topics discussed is the impact of SROs, and many report similar experiences to his.

“I just think the money spent on SROs can go to more efficient services that’s way more effective and engaging,” Flowers said.

Others, however, support keeping the officers on school campuses.

Gonzalo Rucobo, founder of Bay Area Peacekeepers and a self-described “community liaison,” has been working with Richmond High students at risk of being impacted by crime and violence for the last 15 years. He argues SROs are necessary to keep school sites safe.

“The reason we need those police cars out front is not for the kids inside, it’s for the ones who want to get our kids,” Rucobo said during the council meeting.

Rucobo says having an SRO who is trained in community policing on campus can make a big difference on the school culture.

“It takes a person that cares about the community and that cares about youth,” Rucobo said in an interview. “An officer that has the skills to be able to de-escalate and talk things out.”

Rucobo sees other benefits to having SROs on campus, including demonstrating positive relationships between law enforcement and students.

“When they get outside, the message is hate police, and police kill us, and all this stuff,” Rucobo said. This way, they might “get to see [an] officer that’s not trying to kill them, not trying to put them in jail, and actually communicating with them.”

While SROs aren’t allowed to discipline students for behavioral issues and non-dangerous classroom disruptions, according to unit supervisor Sgt. Lynette Parker, officers do arrest students on a monthly basis.

“We’re arresting them for possession of brass knuckles, knives, drugs,” Parker told the city council. “We’ve had every situation happen on a high school campus that happens on the streets.”

Rucobo said SROs are needed in schools because it allows for a quick response to situations needing law enforcement.

Myrick said that the city would likely cover a portion of the SROs bill for now. If the city decides to stop funding for the program, the 13 officers would return to regular street assignments.

Richmond police Chief Allwyn Brown says that means calls from schools would be responded to in the same manner as any other call that comes over an officer’s radio.

No Comments