15 Jan City Council Bans Coal Storage, Selects Districts

By Edward Booth

The Richmond City Council on Tuesday approved an ordinance banning coal storage in the city while also begrudgingly deciding the city’s future district-based council elections.

The coal ordinance prohibits future land use that involves the storing or handling of coal or petroleum coke, or “petcoke,” a byproduct of oil refining. Levin-Richmond Terminal Corp., the only business impacted by the ban, will have three years to phase out storage of coal and petcoke at the Levin-Richmond Terminal, located in the city’s port.

The Environmental Protection Agency says research shows dust from coal and petcoke can harm a person’s heart and lungs.

Previously, Levin-Richmond Terminal President Gary Levin informed the council that the ban will result in the terminal’s closure and eliminate 62 jobs as a result. At a council meeting Dec. 3, terminal vice president Jim Holland said Levin would have no choice but to seek litigation if the ordinance passed.

The council voted unanimously to approve the ban, with councilmembers Nat Bates and Demnlus Johnson III absent.

The council vote comes roughly a month after a meeting where Mayor Tom Butt postponed the decision after roughly five hours of public comment. Much like that December meeting, the council chambers on Tuesday were filled with people on both sides of the ordinance.

Despite the item not being up for public discussion, members of the public used the meeting’s general public comment period to state their opinions on the matter.

Jason Lindsey, an ironworker, said every candidate on the campaign trail talks about creating middle class jobs and middle class society. Yet, he said, without middle class jobs, it’s impossible to have a middle class society.

Steve Morris, a retired sheet metal worker, said powerful corporations had bombarded people for decades with the message that they could have good jobs or the environment, but not both. He said the state building trades have been promoting the agenda of the fossil fuel industry, which damages effective unionism, community health, and planetary health.

“To have allies, we’ve got to be allies,” Morris said. “An alliance with the fossil fuel industry is exactly the wrong way to go, and it will make impossible the alliances we need to make.”

The council also selected a district map for Richmond’s switch from at-large to by-district elections, and chose three districts that will be up for a vote this year.

The switch occurred after Walnut Creek Attorney Scott Rafferty claimed Richmond’s at-large voting system is racially biased, and therefore in violation of the California Voting Rights Act of 2001 (CVRA) — which made it easier for minority groups to legally claim at-large systems dilute their voting power.

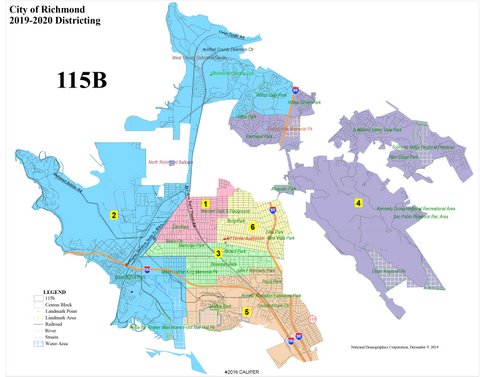

Richmond is set to be split into six regions, with a councilmember representing each region. The council voted to select map 115B, one of six brought before the council, with councilmember Jael Myrick abstaining and Johnson absent.

Richmond is set to be split into six regions, with a councilmember representing each region. The council voted to select map 115B, one of six brought before the council, with councilmember Jael Myrick abstaining and Johnson absent.

The council chose to select 115B over the other maps after several councilmembers and citizens said combining Point Richmond and Hilltop into one district was a mistake on several of the maps. They argued the two communities were distinct and the Point Richmond vote could effectively nullify the Hilltop vote by outweighing it.

Councilmember Ben Choi said he supported 115B over the other maps because it did more to aggregate existing communities together while avoiding needless lines. Eduardo Martinez said he preferred 115B because it didn’t pair North Richmond Heights with El Sobrante, which he said had different interests.

The council also voted for districts 1, 5 and 6 to be up for election in 2020. The other three districts will be up for a vote in 2022, and both will cycle every four years.

Douglas Johnson, president of National Demographics Corporation, explained that if an at-large councilmember with a term set to expire in 2022 is elected to a district that’s up for a vote in 2020, they will vacate their at-large seat and take up a 4-year term as a by-district councilmember. Then, the council will appoint a new at-large councilmember to a 2-year term to fill the vacancy. If the incumbent loses the vote, however, they will remain on the council for two years as an at-large councilmember.

Johnson also explained that if a district is vacant, as district 4 is set to be, they’re represented by the mayor and remaining at-large councilmembers.

Most councilmembers expressed their distaste with how district elections were created in Richmond.

To avoid a costly, likely unwinnable lawsuit from Rafferty — in the range of hundreds of thousands to even millions of dollars — the city moved through a safe-harbor process which limits recoverable fees to $30,000. This means, however, that the process of establishing district elections has been carried out within 90 days.

Bates said he thought the districts would divide Richmond and cause strife. He said that in his long tenure on the council he’d never looked at communities as a representative, and when people called him he didn’t care where they lived. He said that with district elections, the representatives from each region will prioritize their region over the rest of the city.

“I see district elections as probably tearing this city apart,” Bates said. “Unfortunately, we’ve got to comply.”

Other councilmembers were more positive about the concept of district elections, but expressed disagreement with how the process had been carried out.

Councilmember Jael Myrick said he’d been curious about district elections since he came to the council, but he’d always wanted it to come from an organic space, through the community voting for it.

Councilmember Melvin Willis said while he supported 115B, he didn’t know if it was the right decision because voters should have decided if the city should switch to district elections.

“The right way to do this would be to put it on the ballot,” Willis said. “Instead, what we have is a lawyer with a figurative gun to our heads.”

No Comments