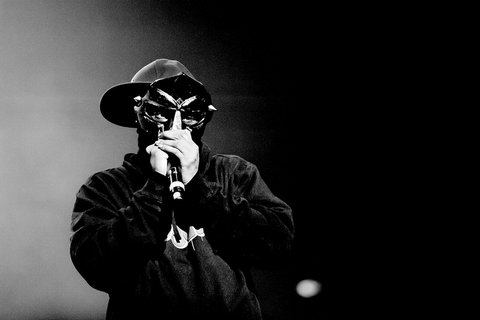

05 Jan MF Doom, a Villain and Champion, Made His Mark on Music With a Mask

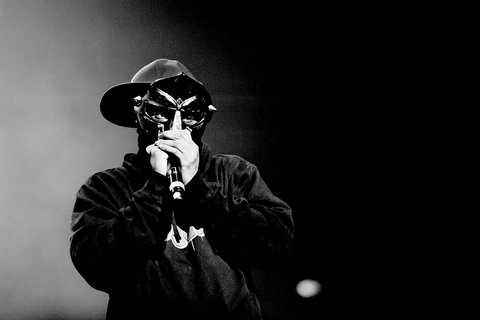

MF Doom performing in Brussels in 2010. (“MF DOOM Live Concert @ Ancienne Belgique Bruxelles-9443” by Kmeron, licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0)

By Joel Umanzor Jr.

As the metaphoric ball dropped, 2020, a year of so much loss, concluded with news of the death of MF Doom, a major figure in underground hip-hop.

The rapper, producer and songwriter born Daniel Dumile died Oct. 31, his wife, Jasmine Dumile, confirmed Jan. 31 in a statement on social media. He was 49.

It is hard to encapsulate what Doom meant to hip-hop.

Doom influenced more than just a track. He was a larger-than-life character among the personas that have come to define hip-hop. He was the music industry’s villain and a champion of those who valued the sport of the music. He delivered lyrics that were technically proficient yet words that were simple enough to provide punchline moments.

The persona of MF Doom appeared first in 1997 with something of a supervillain origin story.

Dumile began appearing at various freestyles around Manhattan, N.Y., performing incognito while wearing a mask. His first masks were simply tights he wore around his face to obscure his identity. Eventually, he coined his moniker and started donning the mask of the famous Marvel villain, Dr. Doom.

As he continued performing in 1998, Doom released several singles and his debut album through hip-hop radio host Bobbito Garcia’s now-defunct record label. His first LP, “Operation: Doomsday,” and his subsequent productions on projects such as his “Special Herbs” instrumental tape helped establish Doom’s fan base.

Dumile released and produced music under other aliases, including Viktor Vaughn and Metal Fingers. He also collaborated with other producers and emcees on side projects.

With producer Madlib, he formed the hip-hop duo Madvillainy. For Doomstarks, he partnered with the Wu-Tang Clan’s Ghostface Killah, who also refers to himself with Marvel-inspired nicknames. Two of Killah’s alternative aliases are Tony Starks and Ironman, a reference to the billionaire character and his superhero alter ego.

The appeal Doom possessed transcended one sector of hip-hop, and the influence on today’s music is undeniable.

What we see in the hip-hop underground, from songs two minutes or less to the use of soulful and complex samples, can be attributed to things Doom did in the late ’90s and early 2000s.

Yet hip-hop artists today cannot replicate the mysterious nature of MF Doom.

Doom never appeared without his mask. This aspect of his persona provided fans and the hip-hop community with a Phantom of the Opera-type character within its ranks.

Like so many of my peers going to middle and high school during the early to mid-2000s, hip-hop became a part of me and my life. I fell in love with the culture that the music provided.

>>>Read: Music at Home: the Sounds That Shaped Us

Although many of us attached ourselves to the regional sound of the Bay Area, we used Myspace, Limewire and instant messaging chat rooms to share music that wasn’t local.

Those early days of social media were the last era of not feeling connected to artists around the clock, and Doom used that to keep himself mysterious and keep his personal life out of the limelight.

So when thinking of how we received the news of Doom’s death, it was not surprising to learn he had died nearly two months prior — and on Halloween, no less.

A man who made his mark on music with a mask left the culture with the same unwillingness to receive personal praise as he entered.

Dumile once rapped, “Living on borrowed time, the clock ticks faster.” He dropped a lot of jewels, but those opening words from “Accordion” will always be the lyrics that I remember first from the myth that was Metal Face Doom.

No Comments