22 Feb Laotian Seniors in Richmond Tackle Barriers to Health Care

Torm Nompraseurt, holding rice and Lao rice baskets in 2020, came to Contra Costa County from Laos as a refugee with his family in 1975. (Evan Bissell / Courtesy of Asian Pacific Environmental Network)

By Isabella Bloom

When his niece died from COVID-19 complications last year, Torm Nompraseurt couldn’t grieve properly.

Before the pandemic, when someone died in the Richmond Laotian community, their family would receive an outpouring of community support. Nompraseurt said there would usually be 50 or more people at the family’s house all the time. During the day, the elders who don’t work would come. In the evening, the working people would come and sometimes stay until 2 in the morning.

People would bring drinks, food, flowers and money for the family. Others offer their labor, volunteering to kill and prepare a pig to eat and to do all of the cooking to relieve the grieving family of any responsibilities.

Nompraseurt has frequently been asked to help prepare funeral arrangements and write eulogies. He interviews the family and learns enough about the person to commemorate them in writing.

“You have the whole community support,” Nompraseurt said. “So you don’t have to be lonely during that sort of time.”

But when Nompraseurt’s 50-year-old niece Saeng Douangsawang died after contracting the coronavirus, that swell of community support could not be replicated.

“Because of COVID, we don’t feel like we had a proper ceremony for her or to celebrate her life,” Nompraseurt said.

Nompraseurt is usually able to accept it and move on when someone dies, because, he said, they respect that God gave them their time on Earth. But without the ability to engage in the traditions that normally comfort him, Nomprasuert said he hasn’t received closure over his niece’s death.

“That is probably the most hit hard to the Laotian community,” Nompraseurt said. “We cannot support each other like we used to before. And it’s so heartbreaking not only for me but for anybody.”

>>>Read: They Lost Their Homes to War. Now, Richmond Laotians Fear Being Pushed Out Again.

The Richmond Laotian community is, by its own description, tight-knit. It formed as Laotian refugees of the Vietnam War came to the United States starting in 1975. These refugees, many of whom are now seniors, make up a linguistically isolated community, and as a result have difficulty accessing health care information. And during the pandemic, long-term health effects of environmental hazards in Richmond put this demographic at greater risk of getting sick.

When the shelter-in-place order was announced in March, Marie Choi, communications director of the Asian Pacific Environmental Network, said the organization’s first concern was “the health of, in particular, Richmond members, because so many people live in such close proximity not only to the Chevron refinery but to other pollution sources.”

APEN is an environmental justice organization with membership bases of Laotian refugees in Richmond and Chinese immigrants in Oakland. The organization focuses on community-based action, empowering community members to fight for the issues about which they care most.

“A lot of the Laotian community members in Richmond already have underlying health issues that they are struggling with,” Choi said. “And so we knew that they were going to be at a higher risk for COVID.”

Refinery fires in Contra Costa County since the 1990s have caused health problems, particularly respiratory ones, that compound people’s risk for the coronavirus.

“It was a common experience for folks to grow up where they and their peers or they and everybody in their family has asthma,” Choi said.

In 2012, the Chevron Richmond refinery explosion and fires put more than 1,700 people in emergency rooms.

“There are people who are still experiencing health impacts from those incidents, who have severe migraines, who have respiratory issues,” Choi said.

The First Laotian Senior Center in the Bay Area

In 1975, Congress passed the Indochina Migration and Refugee Assistance Act to aid refugees from Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos in resettling in the U.S. From 1975 to 1985, about 760,900 Southeast Asian refugees made their way to the U.S.

In response to a second wave of refugees, President Jimmy Carter signed the Refugee Act of 1980, allowing 50,000 refugees into the U.S. per year.

Sary Tatpaporn was a telecommunications officer with the Laos army who escaped to a refugee camp in Thailand in August 1975. After four years in the refugee camp, Tatpaporn applied to immigrate to the U.S. He arrived in Northern California on Nov. 4, 1979, with his wife and 1-½-year-old son.

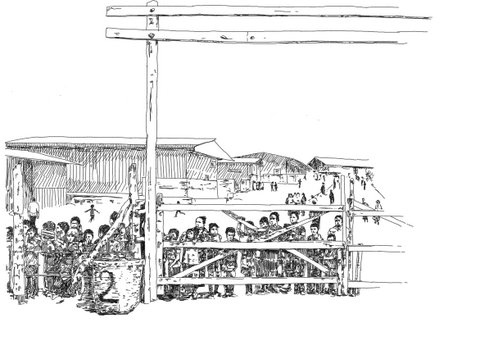

- Drawing of the Thai Refugee Camp where Sary Tatpaporn lived from1979-1981 after fleeing the war in Laos (Evan Bissell / Courtesy of Asian Pacific Environmental Network)

As Tatpaporn, who’s in his mid-60s, grew older, he noticed something lacking in Richmond: There were no accessible information dissemination systems for Laotian seniors.

“I think because of the culture, because of the language, the ability to be able to relate to the other non-Laotian, non-Asian people, they just don’t go, don’t use the mainstream senior center,” Tatpaporn said. Instead, “they heavily depend on their adult children to accommodate them.”

So in 2019, Tatpaporn opened the first Laotian senior center in the Bay Area, providing transportation services and health education.

Each day, an average of 38 seniors would visit. The center was a way for seniors to receive health care information that is otherwise difficult to obtain because of the language barrier.

Because there are several Laotian ethnic subgroups, including Lao, Iu Mien, Khmu, Tai Dam and Hmong, health care materials aren’t always translated for all Laotians.

Megan Zapanta, the Richmond organizing director of APEN, said translation is only the first step to information accessibility.

“We also have members that aren’t necessarily literate,” Zapanta said. “And so even if the materials are translated into different languages, they may not actually get access to that information.”

As refugees, poor education and the disruption of war may now also affect older Laotian generations’ ability to access health care information.

“A lot of people are coming in with pretty low educational backgrounds,” Zapanta said. “Starting here is not easy.”

Tatpaporn’s senior center filled a need in the Laotian community. But when the pandemic hit, senior centers were forced to close. Now, when Laotian seniors need information the most, during a pandemic fraught with misinformation, they have nowhere to turn.

How Laotian Seniors Stepped Up

Torm Nompraseurt said he was part of one of the first Laotian refugee families to settle in Contra Costa County in 1975. He’s been involved with the local community ever since.

As shelter-in-place prevented in-person gatherings, Nomprasuert began creating informational videos about the coronavirus in Lao and making them available to his community.

“Torm Nompraseurt — our senior community organizer — he pulled together a network of Laotian leaders in Richmond,” Choi said.

This network came out of longstanding relationships between leaders who had been working together for a long time. “It was like service providers, social workers, temples, churches and, you know, organizations like APEN.”

To fill the information gap in the community that the pandemic created, Nompraseurt began facilitating meetings with the Laotian Leader Network, which includes about 15 other Laotian ethnic and tribal leaders and organizations.

“People don’t know what to do because they want to talk to each other, they want to connect with each other. And so somebody asked me, ‘So what are we going to do now?’ ” Nompraseurt said. This inspired him to set up the biweekly Zoom meetings. “We can still talk and discuss, especially, the COVID issue.”

>>>Read: Community Outreach Groups Are in ‘Uncharted Territory’

Tatpaporn is one of these leaders who meets with city and county officials and then translates the information to his community and the Laotian Leader Network.

“I try to connect with each in a different group. My role is just like a middle man,” Tatpaporn said. “And then they become like a link between the community and the outside of the community.”

Sharing information by word-of-mouth is common among the Richmond Laotian community.

Nompraseurt said each ethnic subgroup community uses a phone tree system. For instance, if someone were to get sick and go to the hospital, a relative would contact their community leader whose two or three assistants would call 10 other families who continue to pass on the information to the entire community.

Zapanta said this phone tree system is also being employed at APEN.

“We’re trying to really set up, especially during the pandemic, like a call leader kind of system,” Zapanta said. “A phone tree system is one way that we can not feel like it relies on like one person to get kind of the whole base, but really that we have community members that are prepared to help disseminate information.”

Recently, a major concern in the community has been access to food. Although there are emergency food pantries and food banks in Richmond, the staple food for Laotians is sticky rice, which isn’t as readily available.

“The one thing that people wanted and that everybody needed and wasn’t necessarily getting somewhere else was rice,” Choi said.

So APEN teamed up with the LLN by providing money for the leaders to buy 200 25-pound-bags of rice to distribute to their communities.

“We concentrate on raising the money to buy rice and distribute rice to the people, to the family, because rice is the main item,” Tatpaporn said.

Even though Laotian seniors have worked tirelessly with local organizations to meet their community’s needs, Tatpaporn said he wishes there was more help.

“I just want to see more help, more assistance from government or other organizations to help our community, especially [with] the food,” he said.

No Comments