15 Jun Families Desperately Await Schools to Open

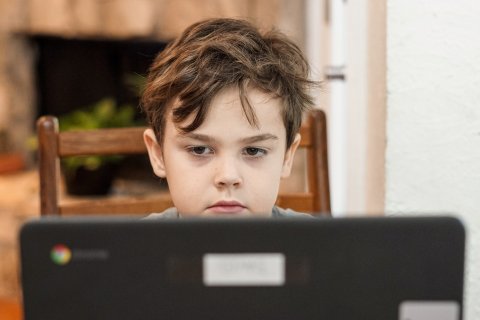

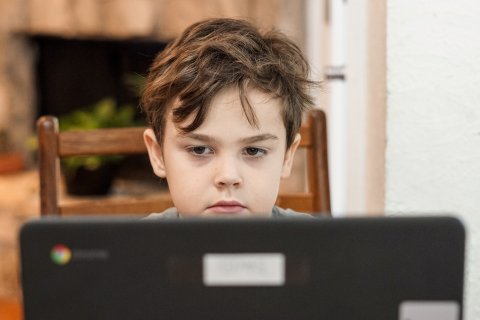

As kids struggle with distance learning, their parents say the return to in-person schooling can’t come soon enough. (Thomas Park on Unsplash)

By Joel Umanzor Jr.

Dropping her kids off at school used to give Leslie Roque time to work on herself and her mental health.

She would do errands during the day while her boys — 7-year-old Anthony and 11-year-old Jerry — were in the classroom. The ability to focus on the needs of her household helped her cope with depression and anxiety.

“I really don’t have that time for myself anymore. The only time I have for myself is when they are asleep or when I’m in the bathroom, but even that is impossible because I always get that knock on the door,” she said, “which sucks because it messes with my mentality, my anxiety and stress.”

Roque, a 27-year-old single mother from San Pablo, has seen this time for self-care decrease over the past year and a half since her children’s education has been confined to their home.

“I have days where I have no choice but to sit there next to them to make sure that they are sitting there in front of their computer, paying attention to what the teacher has to say,” Roque said. “It limits the time I have to do stuff around the house.”

She said that constant surveillance of her children during school hours makes her feel like she has to sacrifice smaller, more personal tasks during the day like making her bed or going grocery shopping, which has drastically affected her mental health.

As the school year comes to a close, students, parents — like Roque — and teachers alike in communities of color have shared these frustrations during distance learning with many looking forward to full-time in-person instruction once again this fall.

>>>Read: My Kids and I Are All Distance Learning. Something Needs to Change

The aftermath from this past year and a half of e-learning could very well have an impact on the educational system in the United States and how it affects communities of color.

Distance learning during the pandemic has had a far-reaching impact on the majority of families across the United States. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, 93% of households with school-aged children were involved in some form of distance learning during the COVID-19 stay-at-home orders.

Molly McManus, a professor in San Francisco State University’s Department of Child and Adolescent Development, said distance learning has affected one of the primary ways children learn: through the physical interaction they experience during in-person instruction.

“They learn with their bodies,” McManus said of young children. “Touching things and interacting with things, including other people, which is a big factor in the early grades. The socialization and learning what it is like to be in a community outside of their families.”

Roque said her son Anthony — a first grader with autism — has been affected by the lack of in-person interaction with other children, yet he didn’t qualify to be in his school’s incremental return to the classroom this spring. Anthony will have to wait until August to be inside a classroom again.

Roque said the lack of personal interaction has also hurt communication between herself and the teachers. That made it difficult for Anthony’s teacher to get to know him and his needs as a student. When he was in kindergarten last year, she said Anthony graduated from the school’s inclusion program — which gave him one-on-one instruction outside of the classroom — but his first grade teacher didn’t know he was autistic.

“What I see Anthony struggling with is more with the social interaction, which I feel like that’s what he misses,” Roque said. “And it’s hard to get that because he is not physically in school.”

What does Anthony say he misses most about school? Playing with other kids.

“I like school at school because of the playground,” he said, reminiscing about the beginning of his kindergarten year.

Part of his and his mother’s frustration is the imbalance created when school and home are the same space.

Kenneth Bonner, principal of Lake Elementary School in San Pablo, said teachers and administrators have also felt the brunt of this imbalance and have had to learn new techniques to fix those issues.

“I think all of us are trying to balance when your home life and your work life or school life now collide in one space. It has been really difficult trying to maintain different areas,” Bonner said. “Like, this is where I’m trying to work, and this is what I’m trying to do from my home, and so I think that has impacted not only my staff but students as well.”

Schools that serve communities of color like Lake in the West Contra Costa Unified School District are facing an unprecedented period, according to McManus. That applies across the district, where, as of 2017, 52.5% of enrolled students were Hispanic and less than 11% were white, according to the U.S. Department of Education’s Civil Rights Data Collection.

McManus said there’s concern that the reaction to lower test scores among students of color could make things worse for them unless the underlying historical lack of access and engagement is addressed.

Lydia Mendoza said she has trouble keeping her 8-year-old daughter Ellie, a student at Aspire Richmond Technology Academy charter school, on track while doing school in a familiar setting.

“It started getting challenging because there were so many distractions at home. She didn’t want to join or she was logged in but also watching TV or on her tablet. So it started getting challenging,” Mendoza said. “There were times where she didn’t want to join, where it was boring for her and what I noticed too was it wasn’t just her. It was a lot of kids and the teacher would have to stop the lesson to tell them, ‘It’s not time to play; it’s time to listen.’ So it started getting challenging a few months into the lessons.”

Ellie thinks often of being back in the classroom.

“I really wish I could go back to school, so I could see my friends, and see my teacher, so I can learn in person,” she said, adding that she didn’t feel like her teachers were able to be there for her as much as they were before distance learning began.

Although the challenges of distance learning have affected everyone involved, parents in communities of color, especially, feel a lack of support and have had to look elsewhere to keep their kids from falling behind.

Roque said she has invested what little money she has in private tutoring for her oldest son, Jerry, because he has fallen behind, even with her sitting right beside him to make him do his work.

“I’m here, and I feel like they are still not learning,” she said. “I’m paying almost $400 a month to get Jerry into tutoring. That’s how bad it has gotten for him in the past year. He, right now, is my struggle because he just sits in front of the computer and won’t engage.”

The lack of support for students, parents and teachers during distance learning, McManus said, has caused a difficult relationship among all involved.

“I think that one outcome of this lack of support is that in some ways it has really pitted families against schools,” she said. “Families were desperate for schools to open again and schools were frustrated that families didn’t understand that this wasn’t safe for their teachers and there was that dynamic — if you zoom out — that neither group had the resources to do what needed to be done and there needed to be some kind of government intervention to help families stay home or give students the resources to reopen safely, but none of that happened within the last year.”

Bonner, like many education administrators, had to combat that lack of support and tried to do even more with what little he had been given. That included collaborating with staff on what works and what doesn’t over virtual teaching evaluations and one-on-one meetings.

Friday staff meetings include a 90-minute call where people can “solidify what’s happening and going on, so that’s been really great,” Bonner said. For teachers, there’s also a 90-minute session dedicated to instruction and how kids are doing in English or math.

Taking lessons from virtual classrooms, Bonner said he hopes to stop over-communicating, instead focusing on being specific and explicit.

“In the virtual environment, things definitely get lost in translation,” he said, “so really making sure everyone is on the same page and everybody understands the same information are things that I will be bringing back with me when we go back into the classrooms this fall.”

For both Mendoza and Roque, the challenge when looking forward to returning in-person instruction in the fall has to do with relearning a lot of old routines.

“It’s going to be hard to get them back into a routine to where they have to get up early, having to get ready and then the traffic,” Mendoza said. “It’s going to be a challenge.”

Roque believes that because school now begins at 10 a.m. — not the traditional 8:30 a.m. — there will be a period of readjusting to waking up earlier.

“That’s a big time difference,” she said. “Having them go to sleep earlier than what they do now. Waking them up and hoping they don’t wake up in a bad mood because they have been waking up late this whole time.”

McManus said there needs to be a conscious effort in catering to the needs of students when reentering the classroom. And when they return to the classroom, everyone needs to do their best in understanding the social and emotional support children need and making sure to not penalize children “for what happened the past year.”

McManus said it is important to recognize children are a product of the education they are receiving.

“It’s important to measure and understand where children are so that we can know if there are these big inequity gaps,” he said. “But that’s never a reflection on the student. That is always a reflection on the system — what they are offered and what the opportunities are.”

No Comments