02 Dec A Fort Hood Scandal: Film Recounts Latina-Led Fight Against Military Sexual Abuse

By Suzanne Gordon and Steve Early

Two years ago, Richmond City Hall Plaza was the scene of a protest vigil organized by Estefany Sanchez and her two sisters. Sanchez is a Richmond resident and an Army veteran whose experience of sexual harassment in the military led her to identify strongly with the tragic case of Vanessa Guillén, a 20-year old soldier at Fort Hood in Killeen, Texas.

Guillén was sexually harassed by fellow soldiers, at a base with one of the highest rates of sexual assault, sexual trafficking, suicide and murder anywhere in the military. Her complaints to superior officers were repeatedly ignored before she was killed while at work in an armory on the base. Guillén’s assailant, Aaron Robinson, then secretly moved, dismembered and buried her body, with the help of a civilian accomplice still awaiting trial. After escaping from military custody, Robinson became one of more than 70 suicides at Fort Hood since 2016.

The Sanchez sisters’ Bay Area demonstration was part of a grassroots movement to challenge and change the toxic work environment that many young soldiers encounter, even if they are never deployed abroad or serve in a combat zone.

>>>Read: How I Became Part of the Vanessa Guillén Occupation

Protestors around the country demanded congressional action to better protect victims of military sexual assault and harassment. Some also angrily questioned the targeting of working-class communities by military recruiters, who encourage young people to enlist based on the promise of secure employment, job training, career advancement, and future access to affordable higher education through the GI Bill.

An Oscar Contender?

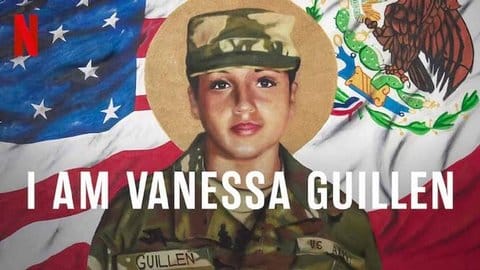

This Latina-led campaign for military justice reform is now vividly recounted in a new movie called “I Am Vanessa Guillen.” Produced and directed by Christy Wegener, the film takes its name from a once-viral hashtag created by Guillén’s family to draw attention to her disappearance, which remained an unsolved mystery for several months in 2020, due to a bungled investigation by the Army.

In the “Me Too” era, Vanessa Guillén’s real-life story will be a strong contender for an Oscar in the documentary category. Its Nov. 17 release by Netflix could not be timelier. Despite promising a workplace free from harassment and discrimination, the Department of Defense just disclosed that nearly 36,000 female service members reported unwanted sexual contact in 2021, a 13% increase over the year before and double the number in 2018.

Other studies have found that one in four women in the military have been sexually assaulted. Even former U.S. Sen. Martha McSally, the first female fighter pilot to serve in combat and a conservative Republican from Arizona, was subjected to such treatment.

An advocacy group called Protect Our Defenders, reports that 44% of the service members it surveyed about their sexual harassment complaints were encouraged to drop the issue. Another 41% said that the superior officer to whom they reported an incident took no action. Despite the steady increase in sexual assault cases, conviction rates have plummeted by almost 60% since 2015. In 2018-19, for example, there were 5,699 reports of sexual assault but only 363 (6.4%) of those cases were tried by court martial, and just 138 (2.4%) resulted in convictions.

“I Am Vanessa Guillen” shows how a vibrant young woman from an immigrant family became the human face of such statistics. She was part of a 21st century influx of women into the armed forces that was initially lauded as an unqualified victory for gender equality. During the last two decades, 300,000 women were deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan and, today, female soldiers comprise 16% of the active duty military. Women are also the fastest growing cohort of military veterans, representing about 10% of a total population of 19 million.

Unfortunately, joining the military has proven to be more harmful than beneficial to many young women. Some who experience military sexual trauma have even been given “other than honorable” discharges which can deprive them of VA healthcare coverage when they return to civilian life.

The uproar over Guillén’s disappearance and death led then-Army Secretary Ryan McCarthy to create an independent panel to determine whether Fort Hood was living up to the Army’s commitment to “safety, respect, inclusiveness, and diversity.” Investigators interviewed more than five hundred female soldiers and found that ninety-three had credible accounts of sexual assault, but only fifty-nine had been reported.

A Fort Hood Scandal

McCarthy agreed there were “major flaws” in a command structure so “permissive of sexual harassment and sexual assault.” The top officer in charge of the 55,000 troops at Fort Hood was removed and disciplined along with 20 others. But thanks to the tireless agitation of Vanessa Guillén’s mother and her two sisters, Congress was also forced to confront the problem of local commanders covering up misconduct on their watch — a phenomena long criticized by U.S. Rep. Jackie Speier, D-Calif., an advocate for military justice reform since 2011.

By May 2021, 60 Senators favored a bill co-sponsored by Kirsten Gillibrand, D-N.Y., and Joni Ernst, R-Iowa, a retired National Guard lieutenant general and past victim of domestic abuse. It would have transferred decision-making power about a wide range of cases, including some hate crimes, to a specially trained team of uniformed prosecutors operating outside the chain of command.

In the Senate, two military veterans on the Armed Services Committee, Rhode Island Democrat Jack Reed and Oklahoma Republican James Inhofe, fought to narrow the scope of the legislation, limiting it to sexual assault cases only. In “I Am Vanesssa Guillen,” Reed makes the factually challenged claim that “the basic instinct of the military is to protect your colleagues and subordinates, not to exploit them.”

In December 2021, after similar pushback from Joe Biden’s Secretary of Defense, Gen. Lloyd Austin, Congress passed a watered-down version of military justice reform. Although it did empower a new cadre of “special victim prosecutors” to handle cases involving sexual assault, rape, murder and domestic violence, court-martial authority was left within the chain of command. At the time, Gillibrand described this compromise as a “disservice to our service members.”

In the film, Gillibrand explains why further congressional action is still needed. “Being able to offer discharges, deciding which evidence is allowed, which expert witness is called, and even just deciding judge, jury, prosecutor and defense counsel — it’s all still sitting with Commander So-and-So.”

That’s why Gillibrand and others in the Senate are trying again to honor the memory of Vanessa Guillén. They have introduced the Sexual Harassment Independent Investigations and Prosecutions Act. It would transfer responsibility for handling sexual harassment cases from military commanders to the new special trial attorneys, who can gather evidence and decide what cases to pursue without political interference.

Hopefully, with or without an Academy Award, “I Am Vanessa Guillen” will keep the spotlight on members of Congress and the Biden administration who fail to provide women in uniform with the additional legal protection they so obviously need.

Suzanne Gordon is a co-founder of the Bay Area-based Veterans Healthcare Policy Institute. She and journalist Steve Early are both Richmond residents and co-authors of “Our Veterans: Winners, Losers, Friends and Enemies on the New Terrain of Veterans Affairs,” from Duke University Press, which reports on the Vanessa Guillén case. They can be reached at Lsupport@aol.com).

No Comments