23 May What’s Changed in Policing in a ‘Post-George Floyd’ America

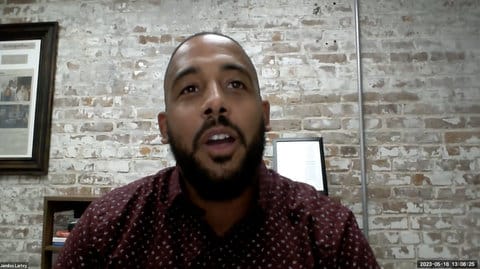

“I think in some ways public awareness around policing almost has to be thought of as pre-George Floyd and post-George Floyd,” said Jamiles Lartey of the Marshall Project during a webinar hosted May 18 by USC. (Screenshot captured by Kelsey Oliver / The CC Pulse)

By Kelsey Oliver

National consciousness around law enforcement has transformed in the years after the murder of George Floyd, leading to new approaches and hundreds of new policing regulations. But even with the changes, reports show that the number of police killings has remained relatively unchanged.

Criminal justice and violence prevention experts joined together virtually May 18 in a webinar hosted by Center for Health Journalism at the University of Southern California on the state of the criminal justice system since Floyd was killed. The panelists discussed law enforcement practices and accountability, community-driven policing and public safety as a public health matter.

Jamiles Lartey, an award-winning writer for the Marshall Project and former reporter for the Guardian covering criminal justice, race and policing, said that national consciousness around law enforcement has transformed in the years after Floyd’s murder.

“I think in some ways public awareness around policing almost has to be thought of as pre-George Floyd and post-George Floyd,” said Lartey. He added that hundreds of state- and local-level police implemented new regulations around police conduct, such as chokehold bans, restrictions on no-knock warrants, and bills that require an officer to intervene if a fellow officer is behaving abusively. In California, Gov. Gavin Newsom passed bills to address police misconduct in 2021, raising the minimum age for officers, allowing badges to be permanently removed for excessive force, dishonesty and racial bias. Standards were also set on law enforcement’s use of restraint techniques that can interfere with a suspect’s breathing.

>>>Read: Questions Remain After Richmond Officers Cleared in 2020 In-Custody Death

Even with these changes, Lartey said the number of police killings has remained at a static rate over the past decade. In 2021, Time magazine reported that U.S. police have killed people at the same rate for the past five years. “What hasn’t changed is the demographic details of these killings,” Lartey said. “Most who die at the hands of the police are white.” However, according to Mapping Police Violence, Black people are about three times more likely than white people to be killed by police.

>>>Read: Antioch’s People of Color Live in Fear of Those Sworn to Protect and Serve

“I think in Minneapolis, there was a deep desire to do violence prevention and alternative work” even before Floyd’s murder, said Sasha Cotton, senior strategy director at the National Network for Safe Communities at John Jay College, referring to the city where he was killed. (Cotton was formerly the director of the Minneapolis office of violence prevention in the city’s health department.) “While that kind of interest is super important and helpful to the field, it also creates a demand that’s difficult to fill quickly,” Cotton said. “So standing up violence prevention work, standing up alternative work, if it’s going to be done well, takes time.”

One way violence prevention can be carried out is by meeting those most at risk for violence where they are. Hospital-based initiatives, where specialists meet at the bedside of an injured patient to discuss recovery and guide individuals away from seeking retaliation, are a path toward unpacking trauma and helping individuals get back on their feet.

Lisa Daugaard, founder of the Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion program in Seattle, discussed her thoughts about taking police out of the equation when it comes to low-level crimes and underlying conditions of poverty, homelessness and addiction that can lead individuals to commit petty crimes in the first place.

>>>Read: Police Adapting to Changing Expectations, Says Acting Richmond Chief

The LEAD model works like this: Rather than an individual entering or reentering the criminal justice system after committing a crime such as shoplifting or selling drugs, they are introduced to social services such as housing, health care, job training and drug or mental health support. An estimated 100 jurisdictions nationwide have adopted this model to divert people away from arrest or incarceration and instead connect them with health services and support.

“The fact is just a lot of people are committing low-level criminal activity in order to get through their lives, to get income, to obtain substances to which they’re addicted, to find a place to live and stay,” Daugaard said, adding that it does not make sense to use punitive enforcement strategies to address issues of poverty and behavioral health.

Panelists brought up other solutions to combat excessive police force and killings, from developing new frameworks around traffic stops, reducing law enforcement deployments and involving officers themselves in discussions around change.

“I think reducing the number of calls for service that law enforcement is deployed to is one part of what we need to be thinking about, but then also identifying the right people to be trusted to work in law enforcement,” said Cotton.

>>>Read: Sheriff Addresses Mental Health Crisis Response

“That doesn’t mean that the people who are doing the work right now are bad,” Cotton continued, adding that some kind of universal guidelines would help frame what is expected from law enforcement.

Daugaard added that people could look to officers for answers around police oversight and accountability, particularly in cases that have escalated to violence. “What is the instruction? What were the stresses? What was this person taught? We need to know why decisions are made, and oftentimes, the people best equipped to explain that are people within the practice of policing.”

No Comments