13 May ‘The Last Bit of Solace’: Disaporic Palestinians Use Music to Bring Support

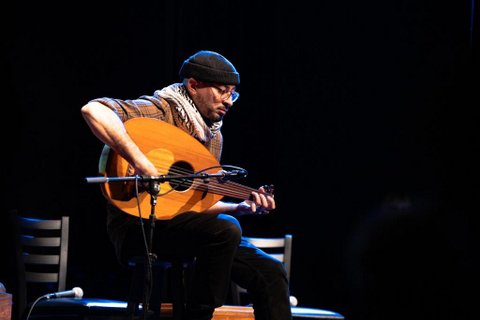

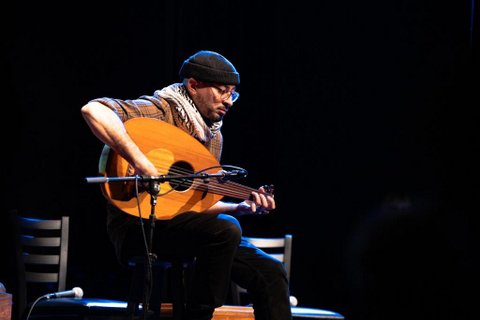

Tarik Kazaleh, a Palestinian American musician also known as Excentrik, plays a Middle Eastern instrument called the oud. (Photo by Jim McCambridge, courtesy of Tarik Kazaleh)

By Samantha Kennedy

Tarik Kazaleh remembered the sounds of the bombs that dropped around his best friend. In the middle of that night, all he could do was play the oud, a Middle Eastern stringed instrument, over the phone for someone thousands of miles away.

Kazaleh watches the suffering of those in Gaza from afar like other Palestinians in the diaspora. Protests and calls for a ceasefire in the Israel-Hamas war are closer to home, but the issue is more than political for Palestinian Americans. It is the loneliness and sadness carried through generations — and those feelings originating in their lifetimes — leading some diasporic Palestinians to use music as a way to cope.

“I was the last bit of solace,” he said. “I’m like, ‘F—, is this the sum of my work — to allay misery?’ ”

Since Israel’s attacks in Gaza and the ensuing international media attention after Hamas’ attack on Israel on Oct. 7, 2023, more than 30,000 Palestinians have been killed. The death and grief are not new. For the Palestinian diaspora in the U.S., which is home to one of the largest populations outside of the Middle East, sympathies for Palestinians have historically been low.

However, as the wave of pro-Palestinian protests on college campuses suggests, attitudes are shifting among younger Americans. Pew research this year found that American adults under 30, particularly those who are Democrats or lean Democratic, are more likely to sympathize with the Palestinian people than the Israeli people. (The reverse is true in both cases among older Americans, and their “views of both Israelis and Palestinians have remain largely unchanged” in recent years.)

Palestinian American musicians are on a mission to keep turning the tide.

Kazaleh, who is now in his early 40s and lives in Martinez, felt rejected growing up between Detroit and the Bay Area. Before becoming one of the country’s first Palestinian American producers and hip-hop MCs, he remembers coming home to his mom after realizing his identity might affect him negatively. Why was he a sand n-word? A kid said so. Why was being Palestinian impossible? A teacher said so.

Sometime after that, as he faced additional rejection, Kazaleh found the perfect escape — music. It was playing Metallica and ska on the guitar, then, perhaps the most noticeable influence on his early work, listening to Public Enemy and having MC battles with his little brother. He emerged as a rare Palestinian voice in the Detroit and Bay Area hip-hop scenes, with many coming to know him as Excentrik.

Using his voice as a Palestinian artist, he says, is a way to inspire those who might otherwise feel isolated.

“We need more people that are willing to stand up and speak,” he said. “That’s why it’s important because no one else is going to do it for us.”

Kazaleh says social media sites like TikTok are a big reason for the growing support of Palestine.

“That gives access to millions and millions of people that would never have seen that brutal, genocidal side of Israel,” he said, “because the American mainstream media will never tell the truth about what apartheid in Palestine is like…”

Other Palestinian American artists say they have faced intimidation and backlash in response to their work, particularly regarding anti-zionist themes, but found a haven in music.

Ten years ago, Camellia Boutros was 19 and teaching music to Palestinian children when she would sometimes stand on a Nablus mountain, watching Israeli missiles go into Gaza. Boutros, who lived in Santa Cruz at the time, visited during the 2014 Israel-Hamas war, during which more than 2,000 Palestinians were killed, where she first learned how to play the oud.

“(The oud) changed the way I thought about music,” she said. Boutros calls it her “heart instrument.” “It’s something about the tone, the way it invites people in.”

The oud is special in Middle Eastern music. The stringed instrument resembles a European lute, though it pre-dates that, and is one of the most commonly used instruments in the genre.

- “That’s how I get through my day,” said Camellia Boutros, referring to music. “It’s a way of transforming something heavy, difficult into something beautiful.” (Photo by Sabrine Rekik, courtesy of Camellia Boutros)

Shortly after Boutros returned to the U.S., she felt paranoid. She had been doxxed by a website that compiles information on anti-zionist college students and faculty, for participating in a meeting to overturn the invalidation of a divestment from companies that were “complicit in the severe violation of human rights.”

Doxxing is publishing the personal information of another without their consent and often with the goal of harming them in some way. Many other Palestinians and their supporters have been doxxed on the same site as Boutros for participating in protests, signing open letters or posting on social media.

“What kind of brought me out of the paranoia was having community around me and realizing I was valued for other things in my life, like my music,” she said.

Music was always in Boutros’ life — piano lessons at 5, guitar at 8; then, a dilemma of wanting to play an instrument everywhere but not having one compact enough at 12 led to the trumpet. It was only after her time in Palestine that her Palestinian identity began to greatly influence her music.

“It was seeping into me,” she said. “Even in my dreams in Palestine, I was getting songs just handed to me.”

After the Oct. 7 attacks, Boutros, now a San Francisco resident, got through her heartbreaks with music.

“That’s how I get through my day,” she said. It’s also how she doesn’t “fall completely in a pit of total depression. It’s a way of transforming something heavy, difficult into something beautiful.”

Kazaleh also took to music in response to Oct. 7, creating the song “Gaza Gaza” with his brother, known as Rithmatik. The song is not just an acknowledgment of the suffering and death in Gaza, but also Kazaleh’s unwavering hope of a free Palestine.

In their political and musical work, which often is intertwined, the push for a free Palestine for Boutros and Kazaleh boils down to equal rights and freedom.

“To be an anti-zionist, to be working for the freedom of the Palestinians is a call, to me, for equal rights for all who call that place home, which is definitely not what the case is today,” said Boutros.

And the two know music is not enough to achieve freedom or to overcome all grief.

“As long as the genocide is continuing and the ethnic cleansing is continuing, the grief is going to continue,” said Boutros. “In that way, you can’t write yourself out of it.”

“There’s also a feeling of helplessness,” Kazaleh said. “There’s a futility to being an artist sometimes.”

Still, that hope remains.

“Over time, we’re seeing more (solidarity),” said Boutros, “and it gives me hope that one day, despite all the injustice that’s happening, there will be freedom and equality (for) Palestine.”

You can find Kazaleh’s music on Spotify and SoundCloud and Boutros’ music on Bandcamp and Spotify.

No Comments