24 Jun One of Richmond’s Own Seeks Full Major League Baseball Pension

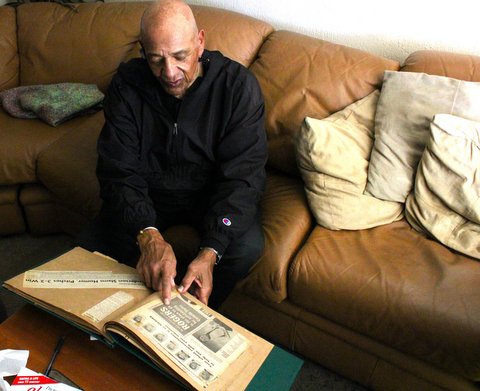

Former Detroit Tiger Les Cain looks at his scrapbook, remembering his baseball-playing days, in his Richmond home.

Editor’s note: This is the first story in a three-part series about onetime Major League Baseball player and longtime Richmond resident Les Cain.

Story and photos by Joe Porrello

A former Major League Baseball player who grew up and still lives in Richmond has been fighting for years for money he believes he earned from the league and its Players’ Association.

Les Cain, who played for the Detroit Tigers in the late 1960s and early 1970s, says he is just shy of a mark that would mean hundreds of thousands of dollars in pension payouts, both past and future. The rules say that accumulation of 172 days of major league playing time constitutes a full season. Four full seasons makes a player eligible for a full pension.

Cain is 43 days short, or so says the MLBPA. He says his service time should be higher.

Other than a baseball-related settlement that pays him $111 per week, annual gratuity checks of S8,000 are all Cain has received — a far cry from the pension he estimates would total around $1.5 million.

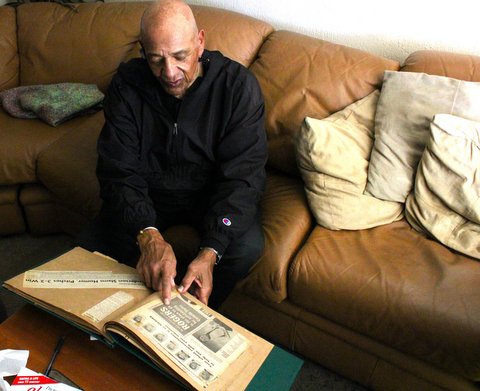

- Les Cain, second from left, says only a handful of the men he played with on the Detroit Tigers over 50 years ago are still alive.

Cain, 76, grew up honing his skills on diamonds in Richmond and throughout the East Bay.

“I was just a kid who loved sports and went to the park all the time,” he said. “I fell in love with the game because of what it meant… purity, congregation and fanaticism.”

Raised on Cypress Avenue and attending elementary school at what is now Kennedy High, he learned the basics of baseball from his father, who played in the Negro Leagues with his twin brother.

He played at Raimondi Park — recently renovated as the home of the Oakland Ballers — as well as Nicholl Park, which he says then was layered in lush green ivy.

Cain’s future as a southpaw was determined long before he stepped on a pitcher’s mound. After severely burning his right arm with hot grease as an infant, he needed skin grafts and favored his left hand moving forward.

His Little League nickname seemed to come from the kitchen too. He was called “Sugar” for his calm and sweet demeanor. But he was willing to get physical, if necessary. “I would always defend myself and my friends,” he said.

Cain learned that life was not always sweet from his parents who faced racism and few job opportunities growing up in Texas and Arkansas long before the Civil Rights movement. Cain’s father, Ell, was stationed in the military at Camp Roberts in San Luis Obispo, then worked in the railroad business in the area. In the late 1940s, Ell moved the family to Richmond because he found better employment at Port Chicago in Concord.

“That’s when Richmond was booming because of the shipyards,” Cain said.

His mother and father warned him of the potential troubles and harshness of life as a Black person in the United States. They taught him “not to hate.” But Cain says he first experienced “true racism” on a family trip to see his father play in Kansas City. A gas station attendant refused to let Cain’s family use the restroom because of the color of their skin.

>>>Read: Proximity: Growing Up in a Multicultural Community Makes Us Less Prone to Racism<<<

Instead of getting upset, Cain’s parents told him, “That guy is miserable. Don’t be like him.”

“If you don’t embrace the negative, you can’t appreciate the positive,” Cain agrees.

The positive of that trip for Cain was, for the first time, seeing his father play professionally and watching him lace a double into the outfield while thousands of fans cheered.

Another person he emulated, plus competed with and often got mistaken for, was his older brother, Ell Jr. — one of five siblings — who also signed with the Tigers. Though never making it to the big leagues, Ell Jr. made it to Spring Training with the San Francisco Giants.

“He was one hell of an athlete,” said Cain.

Cain says he also frequently hung around older neighborhood ballplayers who gave him pointers. At local semi-pro games, he was the team’s batboy. Sometimes, he stayed outside the park, chasing foul balls to sell.

He was friends with Richmond-born legends like Pumpsie Green, the first Black player for the Boston Red Sox, the last team to integrate over a decade after Jackie Robinson broke the MLB color barrier in 1947. “They were very instrumental in my life,” he said.

>>>From Our Archives: El Cerrito Star Signs With UC Berkeley Baseball<<<

Cain experienced segregation on the field himself playing for the Richmond Leopards, a youth team that played other local Black rosters. “Little League didn’t want Black players,” he said. “The Leopards were started based upon the kids from Atchison Village.”

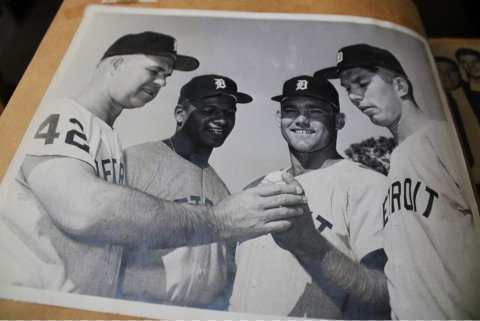

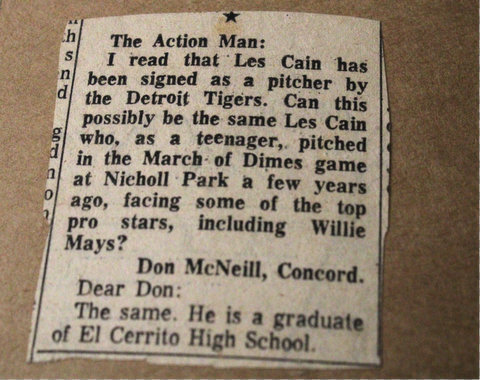

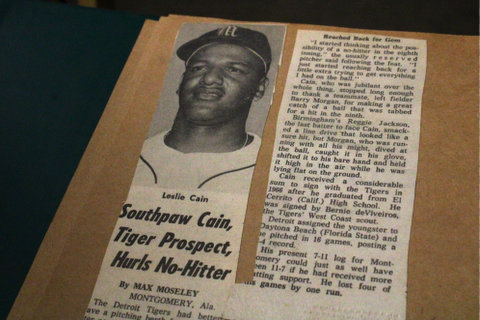

- Les Cain keeps a scrapbook commemorating his accomplishments at all levels, including this article from his early playing days in Legion ball.

Cain began playing with the Leopards after two “mafia-looking guys” — who turned out to be bankers — who ran the team offered him a spot.

At just 14, he began playing semi-pro Legion Ball after acing his tryout — which was held in the middle of the street.

At El Cerrito High, Cain whiffed 20 batters over 10 frames as a junior, and tossed a no-hitter and a two-hit shutout within one week as a senior.

Then, directly after graduation in 1966, Cain and his 100-mile-per-hour fastball were drafted 74th overall in the fourth round of the second-ever MLB draft.

He says he remembers Tigers scouts coming to his home to speak with him and his parents about signing a contract “like it was yesterday.”

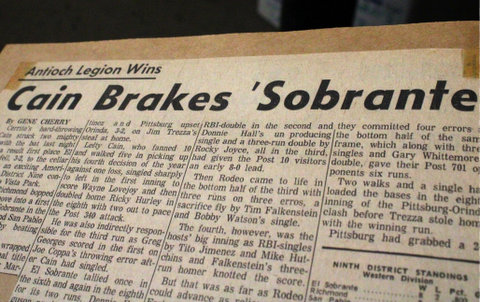

- When a teenage Les Cain faced Willie Mays and when he signed with a Major League Baseball team, one newspaper reader took notice.

His mother was not pleased with Cain’s options to start his professional career: playing Double-A ball with the Montgomery Rebels or the Florida State League Daytona Beach Islanders. Around that time, Montgomery was the scene of Black activists being murdered and rampant Ku Klux Klan activity. Cain says Northeast Florida was not much better.

“It didn’t matter what my mother said, I was a full-fledged employee of the Detroit Tigers,” he said.

Eventually, he played for both teams, often staying with Black families while his teammates stayed in “whites-only” hotels.

At 19, he pitched against players like Mickey Mantle and threw a no-hitter in which Hall of Famer and eventual World Series champion with the Oakland Athletics Reggie Jackson made the final out. That same season, Cain played at Rickwood Field, the oldest professional ballpark in the country, which this month hosted its first MLB game in a “Tribute to the Negro Leagues.”

- Les Cain threw a no-hitter in Double-A — Reggie Jackson made the last out — just as he had done as a high school senior.

After less than two years in the minors, Cain was called up to the big leagues.

Cain had been one of youngest players on the Leopards and his Legion squad, then became the youngest Tiger invited to spring training in 1968, a year after the team finished one game out the the American League pennant race.

His MLB debut came April 28 at historic Tiger Stadium against the even more historic New York Yankees, and Cain was more than ready to live out his childhood dream. Though those dreams did not include fighting for the pension he says he’s earned.

Read Part Two:

‘They Should Have Given Me That Time’: The Transactions that Cost an MLB Pitcher His Pension

No Comments