03 Jul ‘They Should Have Given Me That Time’: The Transactions that Cost an MLB Pitcher His Pension

Editor’s note: This is the second story in a series about former Major League Baseball player and longtime Richmond resident Les Cain.

Read Part One: One of Richmond’s Own Seeks Full Major League Baseball Pension.

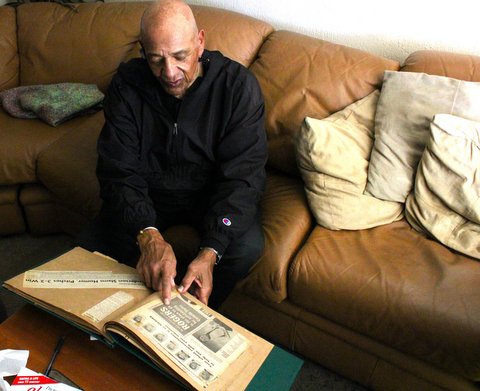

Story and photos by Joe Porrello

Retired pitcher and longtime Richmond resident Les Cain made a storybook debut and had many noteworthy moments in Major League Baseball. But in the end, the realities of the business side of professional baseball have denied him the pension he says he earned.

As the Pulse reported earlier in this series, the 76-year-old Cain receives $111 weekly and $8,000 annually but says his pension should total around $1.5 million.

Cain says he wrongfully was denied service time that would have counted toward his pension at multiple points in his MLB career. That lack of playing time financially squeezed him then too. Plus, it showed he wasn’t as well regarded as he believes he should have been.

After two years of staying with local Black families while most of his minor league teammates in Montgomery, Ala., and Daytona Beach, Fla., stayed in “whites-only” hotels, Cain finally got the call up to Detroit he’d been waiting for.

On April, 28, 1968, at the age of 20, the man nicknamed “Sugar” in Little League dug his cleats into the front of the rubber at Tiger Stadium and took a shutout into the seventh inning against the New York Yankees. He pitched into the eighth and only surrendered one run.

In his first major league at-bat, Cain smacked a double, just as he had seen his father do the first time Cain saw him play in the Negro Leagues.

“I was able to get to a level that he dreamed of,” said Cain. “Everyone said I was exactly like him.”

Despite a serviceable start, the Tigers sent him back to the minor leagues midseason.

He was competing for a spot in a rotation featuring no-earned run averages above 3.70, and unanimous Cy Young winner Denny McLain. That season, McLain boasted a 1.96 ERA to go with 31 wins. No pitcher has won as many as 30 games since.

Cain says it was not his skill that kept him off the roster that year. Despite a signing bonus of $30,000, he only received $2,500 due to a lack of service time. “It was about money,” he said. “If they kept me there eight more days, they would have had to give me the full amount.”

Playing in a pennant-clinching game with the Triple-A affiliate Toledo Mud Hens to end that season, he held the opposition scoreless and got three hits — one of which was a grand slam — to drive in six runs.

Cain says the Tigers assured him he would be promoted in September, but he saw his teammates without bonuses due get called up instead. Then, he watched from home as Detroit won its third World Series in franchise history and one of only two in more than five decades since.

His contribution of eight games pitched with a 3.00 ERA was not acknowledged through the team’s standard championship gifts.

“I thought I was going to get half a (championship bonus) share and a World Series ring… They gave me $200,” said Cain.

To finish 1968, he played in the Puerto Rico Winter League, where Cain threw the 11th no-hitter in league history.

His mother’s death the following year caused him to miss part of Spring Training; he then spent all of 1969 in the minors. Cain began 1970 with the Mud Hens again before getting brought up to Detroit in May. There, he reeled off nine straight wins. He started 29 games over 180 total innings for the Tigers that season, amassing 12 wins and five complete games along with a 3.84 ERA.

- Drafted to the Major Leagues as an 18-year-old, Cain spent formative years with the Detroit Tigers baseball organization.

His 7.77 strikeouts per nine innings were third-best in the American League, and Cain’s 156 strikeouts stood as a Detroit rookie record for 53 years.

After hitting his first major league home run that same campaign, Cain hit his last in the following season — the only one hit by a Tigers pitcher for over two decades.

Despite posting another double-digit win season in 1971 at 10-9, bone chips and a dislocation in his shoulder, to go along with rotator cuff issues, kept Cain from competing at his highest level, and he went back to the minors once more.

Cain says the league’s miscalculation of his number of service days partly stems from that transaction.

He says jobs with pension plans normally factor in time off for being injured. But when he was sent down to the minors instead of being placed on what was then known as the disabled list, it halted his service time credit. “They should have given me that time, but they didn’t give me a full year for that,” he said.

Another notable moment of Cain’s 1971 season came against legendary Boston Red Sox catcher Carlton Fisk. In the third inning of a game Detroit would end up winning 3-2, Cain gave up Fisk’s first career home run, also the first of the 2,356 hits in his Hall of Fame career.

Back in Puerto Rico again for Winter League after the MLB season, Cain became the first pitcher to throw two no-hitters in the league’s history.

To begin the 1972 season, MLB had its first player strike which took another eight days off his service time and cost him $8,000 in salary.

When that season actually got underway, Cain was still dealing with shoulder issues. Pitching in pain, he went 0-3 in five games started. Once again, Cain was not put on the DL but optioned to the minor leagues. He says the transaction cost him an additional 60 games of service time — that time alone would give Cain his full pension, as the MLB Players Association says he is 43 days short.

Shortly thereafter, the Berkeley-raised then-Detroit manager Billy Martin put Cain up against teammate John Hiller — who was dealing with his own physical ailment after having a heart attack not long prior. Whoever had a more potent fastball in the session would stay on the team; the loser would go to Triple-A.

Cain lost. For a third time, he was demoted — instead of being put on the DL — and his service time halted. He refused his spot with the Mud Hens because he was in too much pain to pitch. Instead, he went home to California, where he would stay.

Cain played in Spring Training with the San Francisco Giants in 1973 and 1974 but never made it back to the big leagues. At 24, his career as a baseball player was over.

Before it was over, Cain did start to feel better on the mound. But he suspects the Giants stopped using him because they became aware of his plan to file a lawsuit against the Tigers and wanted to distance themselves.

Battling on the mound throughout his youth and young adulthood, post-baseball life for Cain entailed a different kind of contest — this time a legal fight.

Read Part Three:

Long After Stepping Off the Mound, Les Cain Is Still Fighting for a Win

No Comments