30 Jul Long After Stepping Off the Mound, Les Cain Is Still Fighting for a Win

Retired MLB pitcher Les Cain sits at the Oakland Coliseum to take in an Athletics game in May, which he says “brought back so many memories.”

Editor’s note: This is the third and final story in a series about former Major League Baseball player and longtime Richmond resident Les Cain.

Part One: One of Richmond’s Own Seeks Full Major League Baseball Pension

Part Two: ‘They Should Have Given Me That Time’: The Transactions that Cost an MLB Pitcher His Pension

Story and photos by Joe Porrello

Since he retired from Major League Baseball at age 24 because of shoulder problems, the routine “Play ball!” Les Cain had grown up hearing turned into “Order in the court!”

In 1976, a few years after his playing days had ended, a Michigan judge ruled that Cain’s shoulder injury was the Detroit Tigers’ responsibility and ordered the team to pay Cain $111 per week in workman’s compensation for the rest of his life.

Although the national news was considered a landmark case many observers thought would make teams more cautious about player injuries, Cain says, “Nothing really changed.”

In part two of this series, Cain spoke about the multiple times he was sent to the minors, including times in which he says he was injured.

The judge ruled he was an MLB player at the time of his injury and should have maintained his status instead of being sent to the minor leagues, Cain says. The days of service Cain lost due to being demoted — instead of being put on the major league injured list — would have put him over the threshold to receive an MLB pension that would total roughly $1.5 million.

“You can’t turn your back on what workman’s comp says, because it’s based upon the same injury,“ he said. “They took away or did not give me a year and a half of time.”

Four years of service are needed for Cain to be vested as an MLB player, a total of 172 days for each year including 162 games played and 10 days off.

The MLB Players Association, the athletes’ union, says Cain is 43 days short of his pension. It did not respond to requests for comment for this story.

According to BPI Wealth, the average monthly MLB Pension Plan payout is around $7,500 per month. The pension can be “turned on” as early as age 45, but those who wait until age 62 can receive about $265,000 yearly.

Adding insult to injury, the minimum annual salary for MLB players — the least they can be paid under the collective bargaining agreement between the league and the union — the year after Cain got drafted in 1967 was $6,000, according to Baseball Almanac; today it is $740,000, according to the Associated Press.

After stints in Spring Training with the San Francisco Giants, Cain’s and former Tiger’s teammate Ozzie Virgil — the first Black player with Detroit — introduced him to Horace Stoneham. Stoneham, who owned the Giants for 40 years through their move from the Polo Grounds in New York to the Bay Area, got Cain a job as an insurance salesman — a position he kept for parts of the next 35 years.

Cain also opened three laundromats in the East Bay but sold them and left his insurance job to care for his wife, Vera, who was diagnosed with cancer. Before she died from her illness in 1996 at 46, Vera urged him to start working again.

On her last day alive, Cain passed an exam to become a San Francisco Muni bus driver and did the job for nearly a decade until his daughter, named Leslie like him, died of cancer in 2006. Cain’s made an unofficial pension request came after wife’s death; the second after his daughter’s — neither received replies from the MLBPA.

He says Vera believed the pension Cain deserves would eventually be given to him.

“Do I still think she’s correct? Yes,” he said. “The one thing (MLBPA and Tigers) weren’t expecting is that I’d still be living.”

In 2010, Cain started receiving annual gratuity checks of $8,000, but until he was assured by the MLBPA in 2017 that cashing the payments would not affect his pension, he sent them back with letters detailing his dilemma. The gratuity payments started as a result of a lawsuit filed against MLB on behalf of other players in situations similar to Cain’s.

One of them, Gary Cooper, who played for the Braves in 1980, missed the cutoff by a single day of service.

Cain says unlike a pension, the gratuity checks’ downside is that they do not include any benefits and stop when a player dies, so they cannot pass on to family. Cain’s son and only living direct relative, Brian, turns 55 in August.

In 2018, Cain sent a letter to the MLBPA and says he was ignored again.

The last time he requested his pension was in 2019. A year later, he says he received a letter from an MLBPA insurance company denying his request and was told there was no record of his years of prior inquiries.

If three official pension appeals are made, Cain’s case would then turn to civil court, he says. In the last five years, he has contacted several attorneys about his case but they won’t take it.

“They’re all afraid of Major League Baseball,” he says.

Recently, however, a legal services program out of Sacramento called the Western States Pension Assistance Project took on Cain’s case.

Despite the struggles, the man known as “Sugar” says he’s not bitter. Things could be worse, he says, noting the lives of many inmates he played baseball against at San Quentin prison.

Cain says instead of dwelling on his hardships, he likes to focus on the positives and how far he has come. “You know how Forrest Gump meets the president and ends up in places he shouldn’t be?” Cain said. “That’s how my life feels.”

He credits those who guided and motivated him along the way, like his father and former coaches and players.

“I’m the sum of all the people I’ve run into; that’s who Les Cain is,” he said. “People who care about you are watching you no matter where you go.”

His favorite job was not playing in front of thousands of cheering fans — they were too far away in the stands. Rather, Cain says what he enjoyed more than anything were his jobs that allowed him to talk with people one-on-one and strengthen his emotional intelligence.

As a Muni driver, he says passengers frequently jockeyed for the seat closest to him to chat about their life — Cain doubling as a therapist of sorts. At his laundromats, he learned the schedules of his regular customers and would often greet them with coffee, snacks and conversation.

Looking back on his baseball career, Cain remembers one of his most memorable matchups was when he faced Hall of Famer Frank Robinson and sent him back to the dugout after striking him out with a curveball.

He also points to his relationships with Tiger teammates, a handful of who are still alive. In particular, Cain talked about his bond with Earl Wilson, who died in 2004. “We were brothers until the day he died,” he said.

Wilson is one of 15 Black Aces, the name the late Jim “Mudcat” Grant gave to Black pitchers who had won 20 games in a season, himself included.

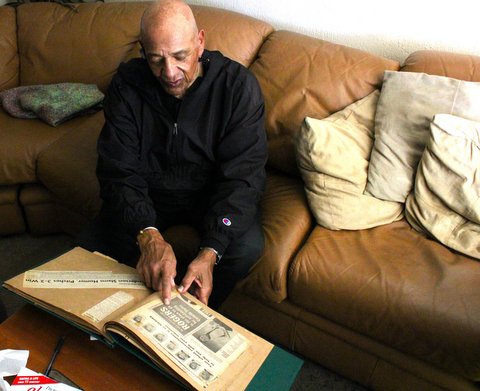

- The East Bay’s own Les Cain, himself a former major leaguer, watches the Houston Astros defeat the not-so-much-longer hometown Athletics at the Oakland Coliseum.

On Mother’s Day (also his wedding anniversary), Cain went to El Cerrito and visited the graves of his wife and daughter, where his name is already on a headstone next to theirs.

The following day, he attended his first MLB game in over two years. (In Oakland, the A’s lost to the Houston Astros.)

“It brought back so many memories,” Cain said.

Cain today is a mellow man who just wants the MLB pension he believes he rightfully earned — and to which he is entitled.

No Comments