30 Oct Rent Control Is on the Ballot Again

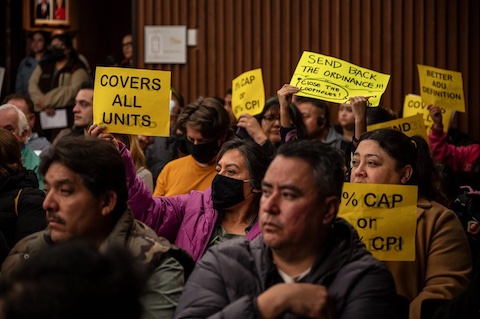

Tenant advocates, landlords and management company representatives gathered at Concord Civic Center for a City Council public hearing amending the “Residential Tenant Protection Program” on Dec. 12, 2023.

Story by Cassandra Garibay, El Tímpano | Photos: Hiram Alejandro Durán for El Tímpano/CatchLight Local/Report for America corps member

As housing costs continue to rise, California voters will decide yet again whether local governments can enact local rent control policies without restrictions in November.

Proposition 33 addresses a significant issue for Latino immigrants, one that was identified by El Tímpano SMS subscribers as one of their biggest challenges: the cost of rent.

California has a long and complicated record with rent control. The Costa Hawkins Act, passed in 1995, halted local rent control on new construction. In jurisdictions that already had local rent control policies, Costa Hawkins made it so that local policies couldn’t apply to housing built after the local rent caps were passed. San Francisco, for example, was an early adopter of rent control in 1979, which meant that housing built after 1979 wasn’t covered under the local rent cap.

The act also limited the type of housing subject to local rent cap policies, exempting condos and single-family homes.

All of that could change in November. If Proposition 33 passes, it would repeal the Costa Hawkins Act entirely. But two previous attempts, in 2018 and 2020, failed to overturn or amend the act, with about 60% of voters voting no each time.

At the center of the struggle are tenants who cannot afford rising prices. How to help those tenants has put housing development and tenant advocates on opposite sides of this proposition, despite widespread agreement that both the development of more housing and renter protections are necessary to end the state’s housing crisis.

Costa Hawkins Act

Under the act, local rent control policies:

- Cannot include single-family homes and condos

- Cannot apply to any housing built after 1995

- Cannot restrict how much landlords can raise rent between tenants

- And for local rent control policies enacted before 1995, they can’t apply to any housing built after the year the policy passed

Latino immigrants feeling the crush of rent in the Bay Area

Approximately 57% of Latino immigrant renters in Alameda County and 63% in Contra Costa County were rent-burdened in 2021, meaning they paid more than 30% of their monthly income to rent, according to the California Immigrant Data Portal. Statewide, about 30% of California renters pay half their income to rent, according to the Public Policy Institute of California.

On Sept.12, El Tímpano asked SMS subscribers, most of whom are Spanish-speaking immigrants in the East Bay, if they had questions or concerns regarding rent increases. More than 70 people responded, many saying they were experiencing annual rent increases, and many also said their wages were not keeping pace with the increasing cost of housing.

Anahy Medina, a mother of two who responded to El Tímpano’s message, said she has rented in Bay Point since immigrating to the United States from Honduras eight years ago. Rising rents recently pushed her, her husband and their children out of a two-bedroom apartment and in with other family members. Medina said she had been renting a two-bedroom apartment for $1,700 about two and a half years ago. A year after she moved in, the rent was raised to $1,800 per month, and this year the rent would have been raised again to $2,000 had they stayed.

“Honestly, it’s affected us a lot because we decided to move,” Medina said in Spanish. “Basically we were working just to pay the rent.”

Medina said her minimum wage salary has not kept up with increases in rent, utilities and other basic goods. Now, she and her family split the rent with her brother for a three-bedroom house in Bay Point.

Medina said she would love to see policies that make it easier for renters and aspiring homeowners like herself to afford housing.

Rent control and California

Landlords in California can only raise rents by 5% plus the consumer price index or 10% each year, whichever is lower, as per a 2019 law. These restrictions apply to all multi-family housing and only single-family housing and condominiums owned by corporations and real estate trusts. And, landlords can increase rental prices as much as they’d like when new tenants move in.

But all housing built in the last 15 years is exempt from these restrictions.

While cities including Oakland, East Palo Alto and San Francisco have long had local rent control policies, in recent years more Bay Area cities have seen soaring rents and subsequent conversations around local rent control.

Contra Costa County, Richmond, Antioch and, most recently, Concord all adopted rent stabilization policies that place tighter limits on how much a landlord can raise rent. Meanwhile, advocates in Pittsburg, Redwood City and San Pablo attempted, but ultimately fell short, of placing local rent controls on the ballot this year.

Because of Costa Hawkins, these local rent control policies only apply to renters in multifamily housing built before 1995. If Prop 33 were to pass, local rent control policies could cover single-family homes, newer housing and incoming tenants if local jurisdictions choose.

Some local governments are already anticipating what this could mean for their communities. The San Francisco Board of Supervisors passed an initial vote on Oct. 8 to increase the number of housing units covered by their existing rent control policies if Prop 33 passes.

- The Housing Action Coalition, which advocates for housing development on all levels of affordability, is opposed to Prop 33 because it could discourage developers from building in areas with tight rent control.

The push and pull of Prop 33

Studies show that rent control policies could have unintended consequences for the housing market. They offer protection for tenants in rent-controlled units. Still, they can lead to landlords leaving the area or dissuading developers from building new housing if the rent-control policies are too restrictive.

A driving force behind California’s housing crisis is supply not meeting demand. According to the Association of Bay Area Government Regional Housing Needs Allocation, the Bay Area must plan for more than 400,000 housing units by 2031. The Housing Action Partnership found a shortfall of more than 58,000 housing units for people making 80% or less of the area median income in Alameda County.

The Housing Action Coalition, which advocates for housing development on all levels of affordability, is opposed to Prop 33 because it could discourage developers from building in areas with tight rent control.

If local governments are given free rein to design overly restrictive rent control policies, the impact on the region could be long-lasting and make it less affordable overall, said Corey Smith, the executive director of the Housing Action Coalition.

“We look at this through a pretty simple lens: Is this going to make it harder to build new homes for people?” Smith said, “and unquestionably, you talk to anybody who builds housing, the answer is yes if Prop 33 is passed.”

A study of San Francisco’s policy published in 2019 by the American Economic Association found that rent control lowered displacement rates for people in rent-controlled units. But the city also saw landlords removing rentals from the rental market. A 2021 policy brief that analyzed California’s 2019 statewide rent control policy, AB1482, found that the statewide rent restrictions would not affect housing growth. Still, more restrictive policies or policies applied to new development could increase risk or perceived risk and affect housing development.

Smith said part of the concern with Prop 33 is that some cities will use it to implement stringent policies to dissuade new housing developments. But some tenant advocates at Alliance of Californians for Community Empowerment and Tenants Together said the concerns about rent control impacting housing construction are overblown and tenants need immediate support to avoid displacement.

- Cities like Concord have recently passed rent stabilization and just cause eviction protections amid increasing concerns about the displacement of longtime residents.

Cities that find ways to block new or affordable housing developments are often the same cities that block rent control efforts, Tenants Together Legislative and Communications Director Shanti Singh said.

“We’ve run rent control campaigns across the state, and those types of cities are the ones who are least likely to pass rent control in any form,” Singh said, adding that the idea that cities will use rent control as a tool to slow or stop development is “a tactic to scare people into voting no.”

Rent control policies can also help immigrant tenants who may not qualify for certain types of housing subsidies and lower the barrier to entry for affordable housing, Singh said. Additionally, as the rental market for single-family homes has continued to grow in the past decade, Costa Hawkins has left wide swaths of the market with little to no protection for steep price increases.

Anya Svanoe, the communications director at Alliance of Californians for Community Empowerment, said that the provision of the Costa Hawkins Act that permits a rent hike when a landlord receives new tenants has led to landlords trying to push renters out by harassing them or refusing maintenance so they can raise the rent for the next group.

Anti-displacement experts have recommended that just cause eviction protections are passed alongside rent control policies, which was the case in Concord. Still, the two policies aren’t always passed in conjunction. The city of Antioch, for example, did not pass just cause protections until nearly two years after a local rent stabilization policy was enacted.

“We see tenants who live in rent-controlled units really have a target on their backs,” Svanoe said. “The issues of Costa Hawkins are really pervasive.”

No Comments