17 Aug Richmond Art Exhibit Keeps Memory of WWII Incarceration Camps Alive

Artist Jeanie Kashima holds up one of 17 collages she made for her first art exhibition. (Photo courtesy of Jeanie Kashima)

By Joe Porrello

During World War II, when her family was forced into an incarceration camp, Jeanie Kashima’s mother had no crib for her newborn, so she placed her in an orange crate.

Nearly 80 years later, Kashima is turning that painful history into art, sharing her Japanese American family’s incarceration story through a 17-piece collage exhibit at the Richmond Art Center.

When President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on Feb. 19, 1942, it granted the secretary of War and military commanders the authority to declare exclusive military regions in the United States.

Though it didn’t specifically mention any demographic, the order became the legal basis for the forced removal and incarceration of more than 120,000 Japanese Americans — most of them U.S. citizens — during the war, according to the National Archives.

During that time, Kashima’s family lived in Berkeley before being confined in a temporary “assembly center” at Tanforan Racetrack in San Bruno along with roughly 8,000 other Japanese Americans for six months.

They all were later relocated and kept in cramped, fenced, and guarded sites at 10 remote areas in six Western states and Arkansas.

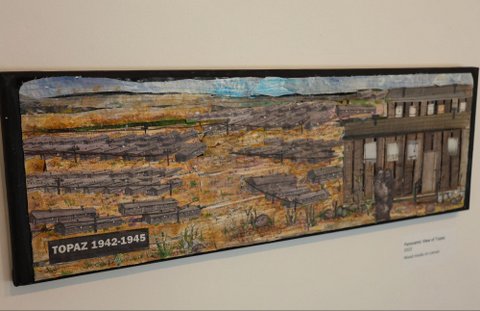

- One of artist Jeanie Kashima’s collages shows the grim sight that was Topaz Camp in Utah, where Japanese Americans were wrongfully imprisoned during World War II, including her own family. (Art by Jeanie Kashima / Photo by Joe Porrello)

Eventually, Kashima’s family was sent to Topaz Camp in Utah. While imprisoned there, Kashima’s mother went into labor before any hospitals were built.

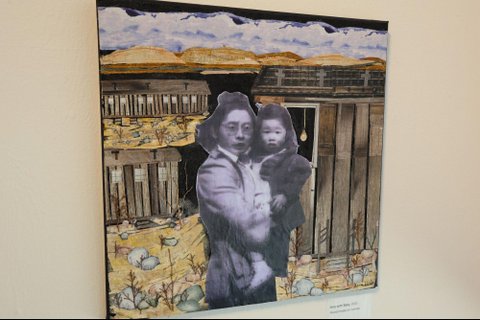

“She had to deliver it in the infirmary, a really primitive kind of situation,” Kashima said. “That baby she delivered was the first baby born in Topaz — and that baby was me.”

Shortly after, in 1946, Kashima’s father died of pancreatic cancer, leaving her mother to care for a baby and two young children alone.

- “Amy With Baby” shows artist Jeanie Kashima being held by her mother in front of the Japanese incarceration camp where she was born. (Art by Jeanie Kashima / Photo by Joe Porrello)

A house in Berkeley owned by Kashima’s grandfather stayed in the family thanks to her Uncle Ernie, who could afford the taxes and repairs, and a white lawyer who helped prevent the government from seizing the property.

“We were lucky — we could have been homeless like many others,” she said. “There were a lot of people that left Topaz who didn’t have a place to go. They stayed in temples and churches and storefronts.”

Kashima grew up in that house, attending Berkeley schools before earning her bachelor’s degree at San Francisco State. The home later became a haven for Japanese students attending UC Berkeley, as racism barred them from renting in the neighborhood.

“For decades and decades, there was such discrimination that the Japanese could not rent in that area,” Kashima said. “It’s still a white area.”

- Artist Jeanie Kashima’s collage shows generations of her family in front of a house in Berkeley they all either lived or spent time in. (Art by Jeanie Kashima / Photo by Joe Porrello)

Kashima married and moved to San Diego, where she had two children. Then she obtained her master’s degree in special education from San Diego State.

Following her husband’s death in 1996, her mother’s death at the age of 104 in 2019, and her children both having kids of their own, Kashima turned to art during the pandemic.

“I wanted to do something and not just waste my time being isolated,” she said. “From 2020 until now has been the most creative period of my life.”

Her interest in art dates back to making collages in high school, taking art classes at SF State, and studying quilting and collage techniques at UC Berkeley. When she obtained rare photos taken by uncles stationed at Topaz — where photography was prohibited — she had them enlarged and used them in her collages.

“Once I had four [collages] done, I really wanted to share them beyond my immediate family,” Kashima said.

Her work was first displayed at the Visions Textile Art Museum in San Diego before debuting at the Richmond Art Center on July 9.

“It never occurred to me that my work would ever be shown in a one-person exhibit, so I’m very pleased to be able to share the story,” Kashima said.

Richmond Art Center gallery coordinator Monica Morazan said Kashima’s proposal stood out.

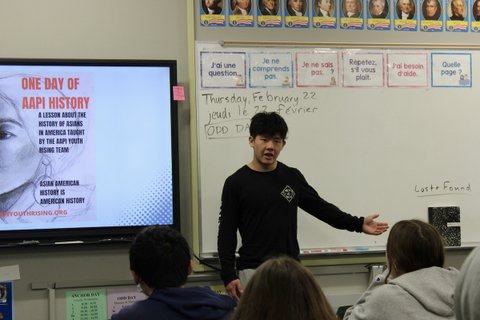

“It’s very personal and it’s so nice to not only see her story; I thought that it would be very educational for younger people,” Morazan said.

The exhibition, “Reassembled Memories,” uses textured collages to depict both the harsh conditions of incarceration and intimate moments from her family’s life.

“I’m getting old, and I want these things to be remembered,” Kashima said. “A lot of people just don’t want to talk about it but I think they should, especially where we are now politically with what’s happening to immigrants.”

According to the New York Times, more than 60,000 people are currently in immigration detention — a modern record, based on Immigration and Customs Enforcement records.

Kashima’s next project will focus on the history of Japanese-run nurseries in Richmond, including one owned by her grandfather Oishi Seizo.

>>>From The Pulse Archives: Threat of Nearby Development Looms Over North Richmond Farm<<<

“When we didn’t have a father all those years, we would come to Richmond for that family support and got a rich childhood,” she said. “They’re all deceased now, but what they did for my family — I want remembered.”

“Reassembled Memories” will be on display until Sept. 6 at Richmond Art Center, which is located at 2540 Barrett Ave., Richmond, CA 94804 and open 10 a.m.-4 p.m. Wednesday-Saturday, except Aug. 30 when it will be closed in observance of Labor Day.

No Comments