23 Oct Richmond Doesn’t Want to ‘Choose Sides,’ Stalls Again on Supporting Tribe’s Bid for Recognition

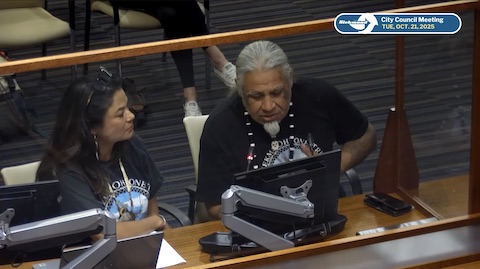

Mukwema Ohlone Chairwoman Charlene Nijmeh, left, and culture bearer Joey Torres again urged the Richmond City Council on Tuesday to support their tribe’s efforts to gain federal recognition. (Screenshot captured by Samantha Kennedy / The CC Pulse)

By Samantha Kennedy

The Muwekma Ohlone Tribe is back where it started with the Richmond City Council: waiting to find out if it would formally back its bid for federal recognition.

Council members on Tuesday put off making that call for a second time this year over longstanding concerns from other tribes that the Muwekma Ohlone’s recognition would erase them.

The tribe says that they’re made up of “all of the known surviving American Indian

lineages” who are native to the San Francisco Bay region and trace their ancestry through the missions of Dolores, Santa Clara and San Jose. That’s in direct conflict with what other tribes, the Confederated Villages of Lisjan, the Tamien Nation, and the Association of the Ramaytush Ohlone, say their aboriginal lands are. (All four tribes are among the modern-day subgroups of the Ohlone people.)

“It would be a colonial violence of erasure,” said Corrina Gould, tribal spokesperson for the Lisjan. “If they get federal recognition, it would erase us from actually doing the work that we have been doing for over 30 years, to uplift the word of Ohlone.”

Supporters, a majority of whom were tribal members and youth from the Indigenous Justice Coalition, backed Muwekma Ohlone Chairwoman Charlene Nijmeh as she asked the City Council to call on federal decision-makers to recognize the tribe.

Federal recognition is a notoriously long and costly process that recognizes a tribe’s right to self-govern and access to resources for housing and healthcare. Only one tribe has been recognized through the process in the last decade. In California, only one tribe received recognition in the process since its creation in 1978.

Support from local leaders is not essential to receive federal recognition, but it can put pressure on lawmakers to recognize the tribe through congressional action. The Bureau of Indian Affairs reported the Muwekma as extinct in 1927, and once the recognition process was created in the late 1970s, excluded the tribe from the list. In 2002, the tribe lost a bid for recognition through the BIA process. In 2022, DNA analysis suggested “that the Muwekma’s connection to the Bay Area goes back at least 2,000 years, ” the New York Times reported, something that refuted the idea the tribe was extinct and was thought to bolster its recognition bid.

But Mayor Eduardo Martinez and council members Claudia Jimenez, Sue Wilson, and Doria Robinson were hesitant to support one tribe’s recognition efforts without including others.

“I think what we don’t want to do is choose sides,” said Robinson. “I want to make a statement and support federal recognition, just not at the expense of stepping into really complex family conflict.”

Robinson with Jimenez and then-council member Gayle McLaughlin suggested a resolution inclusive of the Lisjan, Muwekma Ohlone, and the Ohlone back in January. McLaughlin said at the time she was unaware of a conflict between the tribes and tabled the item.

Nijmeh has claimed for years that the Lisjan, the Tamien Nation, and the Ramaytush are not legitimate tribes, but instead nonprofits.

“Our recognition would not wipe them out because they’re a nonprofit organization. They can continue to do the good work they do for the land,” said Nijmeh.

The three tribes don’t dispute Nijmeh’s tribe’s legitimacy, but they do take issue with her nonprofit and aboriginal land claims.

Quirina Geary, chairwoman of the Tamien Nation, said in a 2022 op-ed that the tribe was “disparaging our name, encroaching on our territory, and appropriating resources that rightfully belong to our people.”

The Tamien Nation and the Lisjan have taken a different approach to federal recognition, albeit a less aggressive pursuit than the Muwekma Ohlone. For Gould, who is also co-founder of the Sogorea Te’ Land Trust, “it does not matter whether or not the government recognizes” the Lisjan. Geary’s tribe will pursue recognition again after the completion of a study.

Martinez focused on creating “one voice” among the tribes, questioning how many powwows the Muwekma Ohlone had participated in in the city.

This year, the powwow committee allegedly refused access because of scheduling, according to the tribe’s culture bearer, Joey Torres.

Torres’ claims are an extension of ones made by an associate of the tribe, who accused one of the powwow’s organizers of erasing the tribe’s presence in two incidents. There was “no serious plan” to include the tribe in the powwow, he said.

“There was no plan to honor them, no invitation to speak, and no effort to recognize their authority or presence on the land where the event was taking place,” he said in a since-deleted statement posted online.

Courtney Cummings Bearquiver, one of the powwow organizers, did not speak on those claims but opposed the resolution because it did not include other tribes in the area.

“When you stifle one voice, you stifle all of our voices,” said Cummings Bearquiver. “There’s a reason why [the BIA] did not recognize them. This is not a job for the city of Richmond to acknowledge them or pass this proclamation. It’s a job for the Bureau of Indian Affairs and our Congress.”

Council members Soheila Bana, who proposed the resolution, and Jamelia Brown spoke in support of the resolution as it was originally drafted.

Council members agreed to have tribes involved meet with Martinez and reconsider the item at the end of February.

No Comments