01 Dec EdSource: Possible WCCUSD Strike Reflects Statewide Tensions

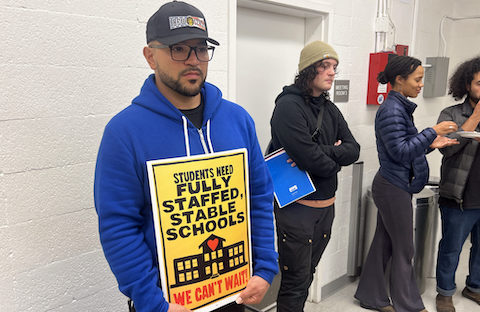

Union supporters attend a community meeting sponsored by the United Teachers of Richmond in Kensington on Nov. 20 to hear about sticking points in negotiations and preparations for a possible strike.

Story and photos by Louis Freedberg

EdSource

Along with at least a half dozen school districts in California, the West Contra Costa Unified School District is struggling to break an impasse in labor negotiations with teachers at a time of declining enrollments and rising costs for both schools and employees.

In West Contra Costa Unified, which includes the city of Richmond and four surrounding communities in the San Francisco Bay Area, the district is bracing for a possible strike that union leaders say they might call this week if their demands for higher compensation and other issues are not met.

In a report issued on Friday, the chair of a three-person fact-finding panel set up by the California Public Employment Relations Board recommended a 3% wage increase for teachers this year and another 3% next year. That is less than the 5% a year sought by the union.

“Little would be gained by pushing the district to jeopardize its financial stability by overly ambitious immediate action,” wrote David Handsher, who was appointed as a neutral arbitrator by the board.

But in an attachment to the report, Mark Mitchell, executive director of United Teachers of Richmond and the union’s representative on the panel, vigorously dissented from Handsher’s conclusions on this and several other contested issues. Francisco Ortiz, president of the union, told his members via email Saturday that there is still a “real possibility of a strike in the week ahead.”

In a statement on Monday, the district said that the report could provide a “framework for an agreement” and that it would not give up on its efforts “to reach a fair agreement” and “to prevent the harm to students a strike would cause.”

As in many school districts, West Contra Costa Unified is struggling to pay all its teachers and other staff in a way that keeps pace with the rising cost of living in California. At risk is the ability of the state’s school system to attract new teachers to the profession and retain the ones it already has.

Several districts stuck in negotiations

In addition to West Contra Costa Unified, at least a half dozen other districts are at an impasse in negotiations with teachers unions: San Francisco Unified, Natomas Unified in Sacramento, Evergreen School District in San Jose, Duarte Unified in Los Angeles County and Newport-Mesa Unified in Orange County. But many more are renegotiating contracts that will expire at the end of June or during the coming year, and further strike threats are possible.

The divides are especially acute in West Contra Costa Unified, with about 25,000 students in regular district-run schools and an additional 4,000 in charter schools, according to last year’s totals. But declining enrollment is having an impact. Ten years earlier, there were just over 29,000 students in district-run schools, and less than 1,500 in charter schools.

The threat of insolvency is not a theoretical one in the district. It was the first in California to get a bailout loan from the state in 1991 and has been on shaky financial ground more or less ever since.

It is currently operating with a structural deficit, which means it is spending more than it is getting from the state and other sources. The only way the district has been able to close the gap has been by making significant budget cuts and drawing down on a special reserve that will be depleted completely by the end of the next school year.

There has never been a teachers strike in the district. A strike was narrowly averted in 2023, when the district awarded teachers a 14.5% salary increase over two years — an increase it was far from clear it could afford.

Since then, how the district copes with the soaring costs of providing special education has emerged as a major issue in labor negotiations — as it has in many other districts.

“It is an issue everywhere,” said David Goldberg, president of the California Teachers Association.

Leaders of the United Teachers of Richmond allege that the district is spending millions of dollars unnecessarily on outside contracts with what it calls “private equity” companies to provide special education services to over 4,000 students with disabilities. Without those contracts, they say, the district would be able to pay its staff fairly.

District officials, in turn, say they have no choice but to hire special education contractors. They point to the well-documented shortage of special education teachers. Students must have the services as stipulated in their Individualized Education Plans, starting at the beginning of the school year, and the district can’t spend months trying to find or train staff to hire in-house, district officials say.

What makes the West Contra Costa Unified labor impasse difficult for the community is that Superintendent Cheryl Cotton is herself a graduate of the district. She took office less than six months ago, saying she believed in the district’s promise and aimed to bring it new hope.

>>>By The Pulse:

Former WCCUSD Student Becomes Its First Black Woman Superintendent<<<

Cotton’s family has lived in the district for generations, as she still does. Her grandfather came to Richmond to work in the Kaiser shipyards during World War II. Her mother taught in the Richmond schools for 42 years. Her great-aunt was a legendary teacher in San Francisco. Cotton herself was a teacher in several Bay Area schools and a longtime principal and administrator in West Contra Costa.

“As a former teacher and principal, I know that those closest to students are closest to the truth of what’s working and what demands our attention,” she said at a recent board meeting, as she appealed to teachers and staff to find common ground.

The district’s associate superintendent of business services, Kim Moses, is also a lifelong resident of the district. She, too, was a longtime teacher in nearby Oakland when she participated in the five-week strike there in 1996, the longest in the district’s history.

“I’d like to be able to compensate all of our staff at higher levels,” Moses told EdSource. “I think every district in California does, but we have to work with the budget we’re given, and have to work together to prioritize and make room in our budget for what’s important to all of us.”

What’s at stake

Ortiz, president of the United Teachers of Richmond, which represents 1,700 teachers and credentialed staff, is the district’s chief negotiating adversary. He worked as an elementary school teacher for 10 years in the district before taking up his temporary union post last year.

He says he has little sympathy with claims that the district is in a financial hole. Instead, he says “a crisis of mismanagement” has been going on for years.

His union is seeking a pay increase of 10% over two years for teachers, plus improved health benefits, among other demands.

Initially, the district declined a pay increase. Its most recent public offer was an annual 2% increase, along with increasing the share the district pays toward health benefits to 85%, up from 80%.

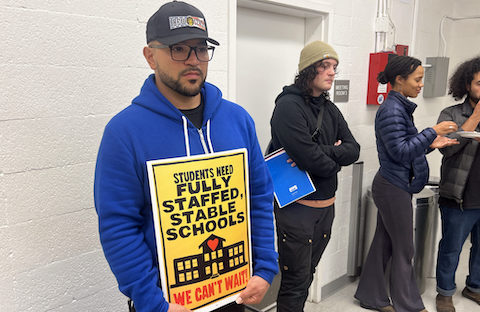

- Gabrielle Micheletti, a first grade teacher in West Contra Costa Unified and the vice president of the United Teachers of Richmond, answers questions from parents about a possible strike at a community meeting in Kensington on Nov. 20.

That offer, Cotton said, would add $7 million to the district’s deficit.

“We made this offer knowing full well it will require significant budget reductions in other areas for us to remain solvent,” she said in her most recent message to the community. “Like a family budget, we can only spend what we can afford.”

The union rejected the offer, calling it “an insult.” But in what may be a hopeful sign that a strike could be avoided, last week the district reached a tentative agreement with Teamsters Local Union 856, which represents about 1,500 non-teaching staff working in food service, clerical, maintenance, and security positions, as well as paraprofessionals working one-on-one with students in special education. That union, like the teachers union, voted overwhelmingly in October to authorize union leaders to call a strike if necessary.

A large part of West Contra Costa Unified’s financial struggles is that in California, fixed costs for districts, on average, go up by 4.5% to 5% each year on necessities other than salaries, such as liability insurance, health care and maintenance, said Michael Fine, president of the Fiscal Crisis and Management Assistance Team, or FCMAT, an independent oversight agency set up by the state.

But the annual cost-of-living increases the state awards to districts is nowhere close to that amount. This year, the cost-of-living increase was only 2.43%. That means school districts fall behind financially “without doing anything,” he said.

But Ortiz, the teachers union president, disagreed with the notion that the district has a financial gap. “There’s no structural deficit,” Ortiz told EdSource. “It’s all nonsense to not support our students and educators.”

He contends that the budgets presented by the district are inaccurate and rejects the conclusions of outside bodies that approve and verify the district’s finances.

Given the gap between the district and the union about the district’s financial picture and possible pay increases, it may be impossible for union negotiators to avoid confrontations with district administrators who were once teachers like themselves, CTA president Goldberg said.

“We don’t have to personalize any of this,” he said. “Just because they were educators doesn’t mean they don’t make mistakes, or need to be pushed, or be reminded just how dire the situation is.”

No Comments