02 Dec EdSource: West Contra Costa Teachers Union Calls Strike for Thursday

Gabrielle Micheletti, a first grade teacher in West Contra Costa Unified and the vice president of the United Teachers of Richmond, answers questions from parents about a possible strike at a community meeting in Kensington on Nov. 20.

By Louis Freedberg

EdSource

Insisting that it is “left with no other option,” the union representing teachers, librarians, counselors and other credentialed staff in the West Contra Costa Unified School District has called a strike beginning on Thursday as it seeks higher wages and an agreement on a range of other issues.

If a settlement is not reached by then in this East Bay district with about 25,000 students enrolled in non-charter schools, it would be the first teachers strike of the current school year in California.

“Striking is the last resort,” United Teachers of Richmond President Francisco Ortiz wrote in an open email Monday night. “We want to teach. But the status quo is failing our students.”

“I understand our staff’s needs and frustration, but I am heartbroken for our students,” Superintendent Cheryl Cotton wrote in a similar late-night email.

She said a strike would not fix the issues raised by the union but could make them worse, including deepening the district’s substantial deficit. And she pledged that schools will remain open, and meals will be served.

California has nearly 1,000 school districts and over 300,000 teachers, most represented by their own local unions, most of which are affiliated with the California Teachers Association.

Despite these large numbers, teacher strikes in California are a rarity. The last major strikes in the state were in 2023, when Oakland teachers struck for seven days, and in the Los Angeles Unified School District, when teachers struck for three days in support of non-teaching staff.

Following the release of a fact-finding report on Friday, the union’s bargaining team met on Monday with district negotiators. The union had already rejected most of the recommendations of David Handsher, the neutral state-appointed arbitrator who wrote the report.

According to a document posted on the union’s website, the district on Monday offered the union a pay increase of 2% this calendar year (effective July 1, 2025) and 1% on Jan. 1, 2026.

That was effectively half of what Handsher recommended in his report — and much lower than the 5% a year the union is demanding.

By late Monday night, the district had upped its offer to 3%, “even though the district is already spending millions more each year than we receive in revenue,” Cotton wrote in her email.

The strike call did not come as a surprise to close observers of the district, who had been predicting one for months.

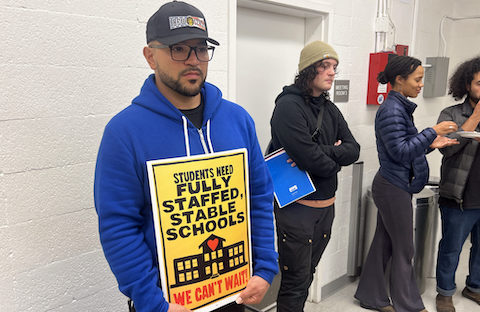

The strike call comes against a backdrop of an intensifying push by unions affiliated with the California Teachers Association. Earlier this year, 32 unions representing about 80,000 educators, including the United Teachers of Richmond, joined a campaign they called “We Can’t Wait.”

One goal of the campaign is to put joint public pressure on school districts, although each contract is bargained separately in each district.

Most unions were able to align their contracts to end on June 30, 2025, and most are currently negotiating new agreements with their districts. Several of them have declared an impasse in negotiations, including Oakland Unified, San Francisco Unified, and Twin Rivers Unified near Sacramento.

The United Teachers of Los Angeles, by far the largest CTA local, has not yet declared an impasse but is threatening to do so.

Plaguing the West Contra Costa negotiations is that the union rejects the notion that the district has financial difficulties, arguing that the district has unspent funds it could use. But district officials say most of the funds the union is pointing to are restricted for specific uses like state grants for community schools.

The arbitrator who headed the fact-finding panel noted in the report that the district had a deficit of nearly $17 million last year. The district’s revenues are largely determined by what it gets from the state based on a formula called the Local Control Funding Formula.

The union has argued that much of the district’s financial difficulties stem from the over $14 million it says the district is paying to outside contractors to provide a range of special education services. If those funds were spent in-house, it argues, the district could afford to pay teachers what they are requesting.

But even if the district could choose not to hire outside contractors, it is a process that would take years to accomplish — far longer than the time it would take to reach a new agreement with its teachers.

The district has posted a fact sheet on its website.

No Comments