19 Feb BART Could Delay Closure Decision as East Contra Costa Faces Transit Uncertainty

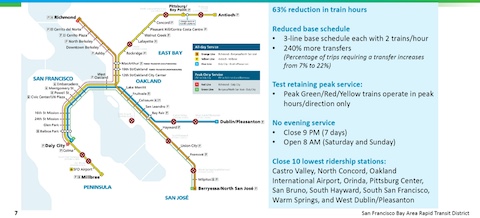

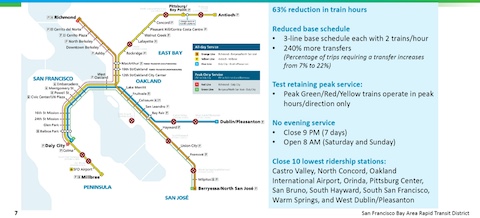

These proposed reductions to BART service — with fewer stations and trains running less often — could become a reality if Bay Area voters don’t approve a one half to one cent sales tax increase on the November ballot. (Screenshot captured by Samantha Kennedy / The CC Pulse)

By Samantha Kennedy

If voters this November don’t approve a small tax increase to fund public transportation, BART could close several stations, including every one in East Contra Costa. But if those closures come to pass, it may be later than previously proposed.

BART had initially proposed shutting down several stations as soon as January 2027 if funding gaps weren’t reduced. But Mark Foley, director of district 2 on the BART Board of Directors, told Pittsburg City Council members Tuesday that the potential closures could be pushed to later in the year. “I met with the general manager [of BART] earlier today, and based on feedback from myself and my colleagues, the concept of closing stations has been moved out of the initial phase,” said Foley ahead of a presentation to officials. “And that’s going to be an option [in] phase 2.”

BART has proposed a two-phase plan that would shut down up to 15 stations, raise fares and reduce the frequency of service to battle a $376 million deficit next year if a tax measure doesn’t pass this fall. The proposed closures could shut down all BART stations in East Contra Costa: Pittsburg Center, Pittsburg/Bay Point and the Antioch stations.

The agency says the deficit is due to declining ridership and fare revenue since the rise of remote work, with record lows happening during the COVID-19 pandemic. BART’s budget uses fares as its primary revenue source.

“That model — while it’s served us well for 50 years — is not the model for the future,” said Foley.

Antioch Mayor Ron Bernal told Foley the day before that the closures would “hugely impact” the region.

According to an analysis of census data by the San Francisco Chronicle, East Contra Costa already has some of the worst commute times in the country. Brentwood, which doesn’t have a BART station, tops that list at 46 minutes; Antioch and Pittsburg are also above 40 minutes.

That’s in addition to Antioch already expecting the closure of another transportation agency’s station in the city.

“And we can’t really afford to not have this type of transportation,” said Bernal in a video with Foley.

Pittsburg officials echoed Bernal’s concerns. Mayor Dionne Adams told KQED’s Forum on Wednesday morning that the service is essential to growth in East Contra Costa.

“A lot of people here feel disconnected [from the rest of the Bay Area], and we’ve been paying to bring BART to this part of the region, so to have those stations close, it evades public trust,” said Adams.

Rashidi Barnes, CEO of Tri Delta Transit, told Pittsburg officials that it’s “still unknown” how his agency would be able to accommodate passengers if closures happened.

To replicate BART’s Yellow Line service, which serves Antioch and Pittsburg, Barnes said BART projected that 120 buses would need to run through the San Francisco Airport station.

If Pittsburg Center were to close and lose riders, Barnes expects that there would also be a reduction in Tri Delta Transit’s ridership and bus lines.

Cuts and solutions

BART and other Bay Area transit agencies are banking on a five-county tax measure that would bring in an estimated $980 million annually for 14 years, according to the Metropolitan Transportation Commission, which coordinates public transportation in the Bay Area. The proposed measure would ask voters to approve a half-cent sales tax in the counties of Contra Costa, Alameda, San Mateo, Santa Clara and a one-cent sales tax in San Francisco.

If passed, the revenue would help reduce the deficits of BART and other agencies like AC Transit and SF Muni. But Pittsburg Vice Mayor Angelica Lopez on Tuesday questioned how BART would remain fiscally solvent.

“Any sort of additional operating funds starts the clock on reinventing how we create a fiscally stable funding model,” said Foley, pointing to programs like BayPass, where schools or employers buy passes in bulk so students or workers can use transit at a reduced cost.

Without the sales tax or alternative funding, Foley said that BART could slash train hours by 63% and increase fares by 30% in the first phase. Trains would stop running at 9 p.m. on weekdays and start running at 8 a.m. on weekends under the plan. Currently, service starts at 6 a.m. Saturdays and 8 a.m. Sundays and ends at midnight every day.

Lopez said that higher fares and riders’ perception of safety and crime around BART — despite a 41% decrease in crime, according to the agency — would likely deter potential riders.

“That’s the challenge — where is that tipping point, where you’ve raised fares too much that you lose riders,” said Foley.

Foley said that the BART Board of Directors is expected to vote on the alternative framework, including the pushed back closures, at the Feb. 26 meeting.

No Comments