12 Oct Health Equity Report Shows Areas of Improvement and Concern for Richmond

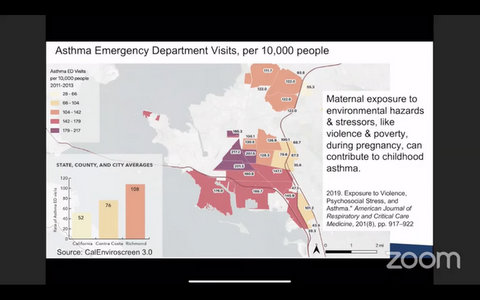

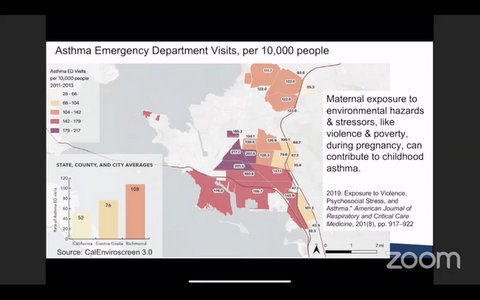

Asthma rates, especially in Central Richmond, are still a problem despite improvements on some health measures. (Screenshot captured by Edward Booth / The CC Pulse)

By Edward Booth

Life expectancy has increased, gun homicides and assaults have gone down, and Richmond has introduced a swath of programs to help improve health equity over the past 20 years. But some measures, such as asthma rates in Central Richmond, haven’t declined as quickly as experts hoped.

That’s according to a progress report given to the City Council Sept. 29 about the city’s health equity-focused Health in All Policies ordinance. (The full report can be found in the agenda documents of the meeting.)

The premise of the ordinance, first passed in 2014, is that decisions made outside of health care and public health systems — areas such as housing, transportation, economic development, criminal justice and education — have a significant impact on health, UC Berkeley professor Jason Corburn said during his presentation to council.

Corburn said the focus of the ordinance is achieving health equity in Richmond, which means that everyone should have the resources and opportunity to be healthy.

“It’s really an umbrella strategy — it’s not one policy — and it really recognizes that health, as we’re seeing right now with this pandemic, it really happens outside the health care system in many ways,” Corburn said.

The 58-page report covers six areas: governance and leadership; economic development and education; full service and safe communities; residential and built environment; environmental health and justice; and quality accessible health, homes and services.

The data used in the report comes from sources including the American Community Survey; CalEnviroscreen 3.0; California Health Interview Survey; the Richmond Police Department; Transparent Richmond; the Richmond Community Survey; and the West Contra Costa Unified School District.

The report also delved into a few case studies for each subject area by covering the background of some of the programs, how they’ve progressed over the years and how they link to health equity.

The Richmond Promise scholarship program, for example, is used as a case study for economic development. It provides scholarship recipients, who are college students from Richmond, $1,500 a year over the course of their college career and guidance on how to navigate and succeed. The report says 70% are first-generation college students and 65% come from low income households.

The report explicitly links the program to health equity in a section that talks about how it helps college-bound students gain the resources to succeed, which, in turn, supports health for first-generation residents and their families by giving them access to well-paying, safe jobs.

“Besides covering costs I can’t afford to pay out of pocket, knowing that the Richmond Promise Team is there for me and will help me continually navigate through the strange world that is the college campus really makes all the difference,” a Richmond Promise scholar is quoted in the report as saying.

The report lists many persistent trends: gun homicides and assaults going down and life expectancy going up over the past 20 years and a stable poverty rate despite declines in unemployment.

Coburn and city staff, gave an overview of each subject area and many of the trends.

Corburn focused early in the presentation on inequalities that still exist, particularly by race and ethnicity.

One statistic that hasn’t improved as much as hoped is the rate of asthma emergency department visits per 10,000 people, he said. He cited a 2019 study in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Medicine that indicates maternal exposure to environmental hazards and stressors, including violence and poverty, can contribute to childhood asthma.

“We know now that things like asthma and many chronic illnesses are not caused by one exposure alone,” Corburn said. “What we know now about the biology of stress, and what we’re seeing also with COVID, is that chronic stress, including racism, can really damage the immune system.”

Coburn said that the city has made significant progress in some areas, including leadership within the city government and partnerships with community-based organizations.

More focused efforts to address racial and health inequities should be considered, according to the conclusions, and public communication of the results should be done in an ongoing way, such as by utilizing Transparent Richmond, the city’s open data system.

“There’s some progress, some real progress,” Corburn said. “Health in All Policies should be seen not as a one-off policy by the city, but really as focusing on health and health equity as something that can be constantly addressed and improved through different strategies that the city has some control over.”

No Comments